Twenty years ago, I had a lot more friends than I have now. This isn’t an anecdote about the circumstances under which I first saw GHOST DOG twenty years ago — although just to get that out of the way, I saw GHOST DOG alone in the smallest screening room at the Angelika, with nobody else in the theater and the rumble of the subways underneath. In retrospect, that was if anything predictive of the future tendency towards isolation I’d adopt and still practice, but back then it was fairly rare that I’d go see movies alone.

What I liked to do, back when I had a few dozen friends, was less to hang out with a regular gang than to mix it up. What I liked to do was mix and match. What I liked to do was jumble up dissimilar personalities to see what sort of chaos or synchronicity would follow. It was barely a conscious decision. I wasn’t that clever. Something instinctive to me was to make plans with my most conservative friend and invite along the class farter, to collide the wallflowers with the hornballs, the real-sex-having Nine Inch Nails kids with the proto-basic Sublime-but-only-“Santeria” kids, the high-achievers with the inveterate dipshits. Sometimes it was a blast (for me) and sometimes it was a disaster (for them). It may even be a solid argument for why a mutant like me should never be gifted with something like popularity.

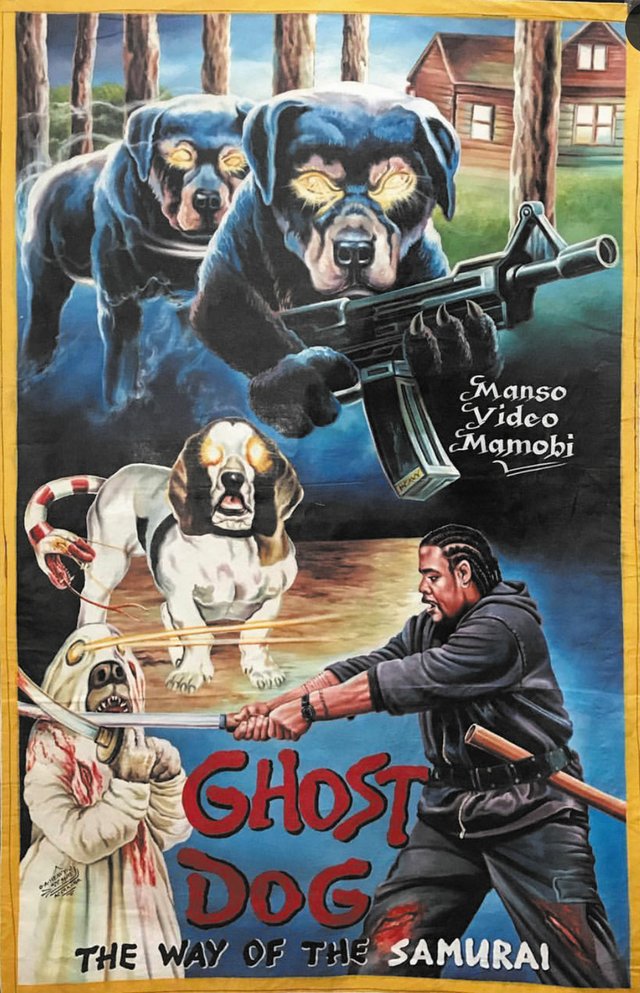

It’s also how I’ve come to think about the movies of Jim Jarmusch, at least the ones I’ve seen to date. In his most memorable work, Jarmusch plays the role of connector, bridging cultures and introducing unique and unlike talents to each other and in the best cases, achieving unusual alchemy. Jarmusch has a knack for assembling casts decorated with iconoclastic weirdos — Steve Buscemi, Bill Murray, Rosie Perez, Iggy Pop, Tilda Swinton, Tom Waits — and letting them meander. I wouldn’t use a potentially dismissive term for them like “hangout movies, but they’re not exactly densely-plotted affairs and there’s not much in the way of spectacle, only fascinating human faces.

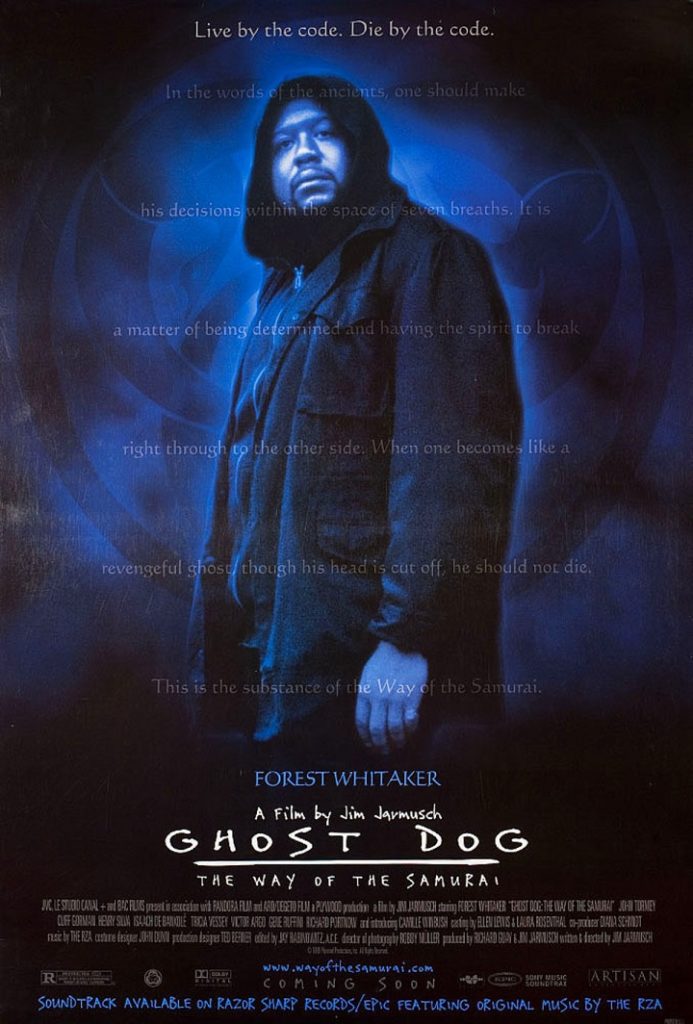

GHOST DOG: WAY OF THE SAMURAI is more structured than most Jarmusch films, due to the conceit of it being grafted to the Hagakure, which the title character reads religiously. It might be that I gravitate more to GHOST DOG than to most Jarmusch films because it’s the closest to commercial — the character of Ghost Dog, an African-American hitman contracting out to the mob who lives an ascetic life of devotion to samurai principles almost four hundred years old, is a natural fit for a premise alert to the longtime affinity between hip-hop and Asian culture. Ghost Dog himself isn’t part of hip-hop culture, but he serves as an avatar meta-textually. Jarmusch’s other stroke of inspiration with the film was to recruit the RZA of the Wu Tang Clan, a scholar of Asian action films.

RZA is truly a co-author of GHOST DOG. His score and his soundtrack choices permeate the film in a truly special way. Ennio Morricone composed his scores so that Sergio Leone could play them on set, and if that’s not how RZA composed his low-key cues for GHOST DOG, it sure feels like it. The music feels as much a part of the creation of this film as the locations or the sets or the script or the acting. If this movie were alive, the music is the feet. By the time RZA himself shows up later in the course of the film as a fellow gunslinger, it feels less like a cute cameo than the score expressing itself in physical form, like the orchestra nodding from the dark pit in front of the stage at the opera hall.

Another everpresent leitmotif of the movies made by Jim Jarmusch, which is as evident in GHOST DOG as anywhere in his filmography, is the theme of communication. There are plenty smarter writers about film than me and I have to imagine they’ve picked this topic to death, but I notice that so many Jarmusch films are about the ways people communicate with each other. Just on the surface, his films are rich with distinctive speaking voices. Forest Whitaker is such an immaculate casting choice for the role of Ghost Dog for so many reasons, not least of which being his soft-spokenness. When he reads from the Hagakure, it’s almost meditative, like you’re listening to a monk, not a warrior. Whitaker as an actor has played his share of flamboyant villains, but somehow, when thinking about this actor, this is a key movie that comes to mind in understanding what makes him so unique. The care that Ghost Dog puts into the pigeons he raises, the ironic kindness conveyed by a character who is a bringer of death, that feels essential.

Again, GHOST DOG isn’t all that heavy on plot. There’s plenty of screen time — and this is a blessing — committed to letting a stable of unlikely characters played by unlikely actors bounce off the central figure of Ghost Dog, whether that be the wonderful African actor and Jarmusch regular Isaach de Bankolé, who plays Ghost Dog’s best friend in the world, despite him not speaking a word of English, or the excellent (then-)child actor Camille Winbush, a girl from the neighborhood whose path crosses with Ghost Dog more than once. Obviously one of the most memorable aspects of the film is probably the mobster characters, starting with John Tormey, who plays the go-between who brings Ghost Dog his assignments and who is so effective at conveying his character’s confusion at the entire existence of Ghost Dog while still carrying genuine affection for him.

Then there’s Cliff Gorman, in real life a former leading man and in this film the consigliere to the mob boss whose iconic moment is singing along with “Cold Lampin’ With Flavor” by Public Enemy from their album It Takes A Nation Of Millions To Hold Us Back. What I love so much about that moment is that while most American movies would play it strictly for comedy — old white guy does a hip-hop, ha ha — without any understanding of why it’s funny, the way it plays in GHOST DOG courtesy of Gorman’s performance is that this guy really loves this song. He may or may not get what the words mean (in fact he definitely doesn’t), but it moves him, and it makes him dance. It’s coming from a more genuine place for the character, and so yeah, it’s meant to be funny, but it’s way funnier than it would be in a more conventional movie.

And lastly but hardly leastly, there’s legendary character actor Henry Silva as the aforementioned mob boss, Ray Vargo. Please enjoy him now:

When I refer to Henry Silva as “legendary,” it’s with the knowledge that he’s legendary in the mind of me and of dozens, maybe hundreds, maybe even a couple thousand hardcore cinemaniacs, but not in the minds of the movie-loving populace at large. That has to change. If you like what he’s doing here, please rest assured Henry Silva is doing something equally interesting and compelling and weird in pretty much every movie he ever appeared in, dating back to the 1950s and ending pretty much here. GHOST DOG was essentially his final film role, barring his cameo in 2001’s OCEAN’S ELEVEN. (He had appeared in the 1960 original.) Getting into the topic of Henry Silva is something I would love to do at length, so be sure to retweet this article all over the damn place and comment below and encourage me to do a column, because Henry Silva is just a beautiful creature whose film appearances ought to be savored and celebrated one by one.

Henry Silva’s performance in GHOST DOG to me is the movie GHOST DOG in microcosm: Bizarre, surprising, winning, a little bit malevolent, hilarious, perfectly pitched, weirdly lovable, impossible to forget, and just as enjoyable every time I return to it. It’s not the easiest movie to track down at the moment — there’s no Blu-Ray and it isn’t currently streaming. I’m lucky enough to have picked up a DVD back when that was a thing, but right now the best bet is probably repertory screenings. You’re going to want to see Robby Müller’s images projected anyway. If it plays near you, I recommend you go, and bring a few friends who hate hip-hop or samurai movies or movies in general — just to see what happens.

- [THE BIG QUESTION] WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE FEMALE ENSEMBLE IN MOVIES? - July 22, 2016

- [IN THEATERS NOW] THE BOY (2016) - January 24, 2016

- Cult Movie Mania Releases Lucio Fulci Limited Edition VHS Sets - January 5, 2016

Tags: Camille Winbush, Cliff Gorman, Forest Whitaker, Frank Adonis, Gary Farmer, Henry Silva, Isaach De Bankolé, Jersey City, Jeru the Damaja, jim jarmusch, John Tormey, Killah Priest, Kool G Rap, Masta Killa, music, New Jersey, Public Enemy, Richard Portnow, Robby Müller, RZA, Shi Yan Ming, Tricia Vessey, Victor Argo

No Comments