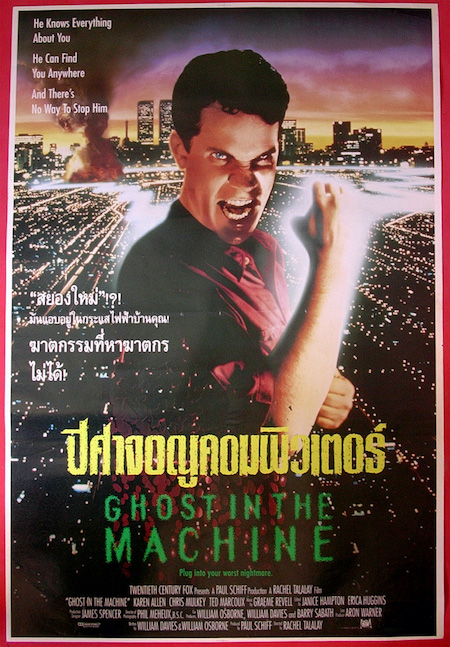

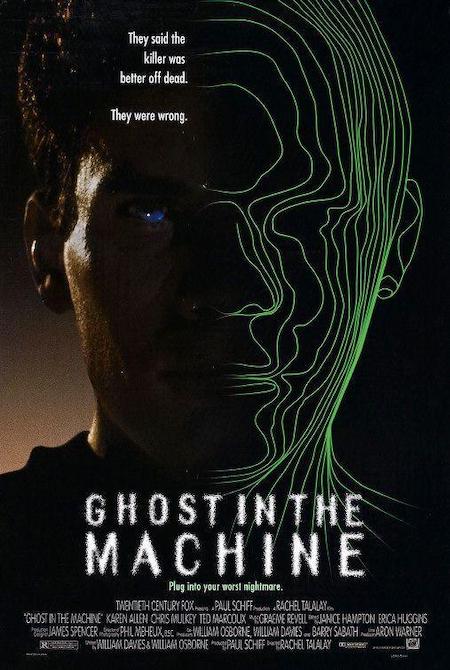

New Line Cinema’s decision to kill off Freddy and Jason left a void in the early-’90s horror scene, creating an odd, sort of listless time for the genre: with the ’80s slasher trend receding further into the rearview mirror each passing year, Hollywood produced a strange grab bag of burgeoning franchises, splatter-era leftovers, and even some last-gasp efforts from the golden age of Stephen King adaptations. Nestled in this eclectic bunch was also a rash of techno-horror films like, and FREDDY’S DEAD director Rachel Talalay herself would step into this arena to fill that Krueger-sized void with 1993’s GHOST IN THE MACHINE.

Obviously, it’s hard to make the case that it did that since it came and went without much fanfare and has since fallen into virtual obscurity. But in an era where genre enthusiasts re-litigate every movie, I think it’s only fair that we extend the same courtesy to GHOST IN THE MACHINE and recognize it as an entertaining attempt to update the splatter movie for ’90s sensibilities. Maybe this means it’s very much of that era, but I’m not sure that’s a bad thing when it involves early visions of virtual reality, vintage hip hop, and reminders that America was once briefly obsessed with crash test dummies.

It also involves the pervasive belief that this budding technology known as “computers” and “the internet” were capable of doing anything, which explains our plot. A maniac dubbed “The Address Book Killer” has been wreaking havoc by swiping address books and using the names found within as targets. By day, he’s just Karl (Ted Marcoux), a creepy computer store grunt who eventually crosses paths with beleaguered single-mom Terry Monroe (Karen Allen).

When she accidentally leaves behind an address book, Karl assumes he has a new smorgasbord; unfortunately for him, he suffers a car accident that leaves him the hospital with brain trauma. Before an MRI can reveal the extent of the damage, a surge from a lightning storm transfers his soul into the internet. Doctors assume he died; however, he quickly resumes his grisly exploits by hacking into electronic devices to murder everyone in Terry’s address book.

Clearly, GHOST IN THE MACHINE requires you to suspend all of the disbelief, especially that we now definitively know that computers are not capable of soul transference. (On the other hand: a psychotic man using the internet to dox and kill innocent people? Super believable, unfortunately.) No, this isn’t some parable about the looming horrors of the computer age; yes, it’s blatant technosploitaiton, a thinly-veiled excuse to hijack this emerging trend and turn it into a splatter movie. And that’s okay. Besides, it’s not the first time this genre would ask us to just go with it. Last I checked, it wasn’t possible for a dead child-murderer to butcher you in your sleep, and let’s not pretend that other slashers didn’t thrive on exploitation.

To that end, GHOST IN THE MACHINE mostly works, especially when it gets down to the nasty business of offing its expendable cast. Talalay carries over the imagination often harnessed by the ELM STREET series here by staging imaginative and deviously clever murder sequences. The premise here dictates more than routine stalk-and-slash, and Talalay obliges with inventive theatrics to indulge that familiar sense of audience bloodlust inspired by slashers. Her camera darts and whirls through a network of cables and power outlets to give a presence to her phantom killer.

Dynamic shots capture the elaborate set-pieces that unfold with a demented, insidious intent: various appliances—dishwashers, microwaves, hand-dryers, crash test dummy sites—become twisted pieces of a gory jigsaw puzzles that lead the audience to guess at just how Karl will dispatch his victims.

FINAL DESTINATION would go on to popularize the formula on display here, but GHOST IN THE MACHINE did a fine job of it seven years earlier. Not only are the set-ups playfully tense, but the pay-offs provide an outlandishly gruesome assortment of melted skulls, electrified teenagers, and even a complete full-body torching. I have a policy of appreciating any movie that features an unhinged fire stunt, if only because it reminds me that someone put their life on the line for my entertainment. Someone lit themselves on fire in the service of GHOST IN THE MACHINE, and, for that, it has my enthusiastic endorsement.

Your mileage my vary, of course. There’s definitely an argument that GHOST IN THE MACHINE has a little bit too much of a mean streak to be considered one of those harmless, goofball slasher movies. All of Karl’s victims are as innocent as they are disposable, meaning you can’t glean any satisfaction from their deaths, nor are you all disturbed by them since most appear only to die.

Consider the case of Carol Maibaum (Shevonne Durkin), a babysitter whose only “sin” is briefly flashing the two boys (Wil Horneff and Brandon Adams) she’s charged with watching. Dog lovers should also beware because GHOST IN THE MACHINE has no qualms about disposing of anyone or anything for pure shock value. Even a poor old grandma (Jessica Walter?!?) isn’t spared Karl’s wrath when he manipulates a SWAT team into firing live rounds into her home.

It’s also fair to say that the downtime between the slashing isn’t the most compelling. The presence of Karen Allen and Chris Mulkey (playing an IT wizard who assumes all the shenanigans are the work of an expert hacker) give this nonsense the faintest sense of gravitas, and the major studio production values lend a gritty sort of legitimacy to the proceedings. But there’s a sense that it’s all just window dressing for the splattery spectacle.

Whatever drama GHOST IN THE MACHINE has leans on the tense but clichéd relationship between Terry and her unruly teen son Josh (Horneff), and even this is underserved. It mostly amounts to him mouthing off, eating an enormous pile of Oreos, and racking up an absurd bill on a sex hotline, while his poor mom’s only recourse is to take away his landline phone. Truth be told, his buddy Frazer (Adams, PEOPLE UNDER THE STAIRS) is the badass little kid Josh thinks he is, but he’s unfortunately reduced to a sidekick role here. Still, try not to crack a smile when Frazer’s hustle involving the babysitter works out, producing one of the most wholesome shit-eating grins imaginable.

I wish there were more moments like that, but the script isn’t that invested in these characters. They mostly exist to investigate and unravel a plot that’s already plainly unfolded for viewers, who are left waiting for everyone to figure out that Karl is an internet phantasm, not a hacker boogeyman.

The effects take a higher priority, as best evidenced by a memorable sequence where Josh and Frazer visit an arcade that features a state-of-the-art VR sim, which allows Talalay and company to dabble in some primitive computer effects when Karl stalks the boys within the game. At the time, this technology was aspirational, or at least it was to me, an absolutely impressionable 10-year-old who thought virtual reality was just a few years away. 1995 and the crippling disappointment of the Virtual Boy hadn’t arrived yet to crush those dreams.

Nearly three decades later, these effects feel dated and chintzy, but you have to admire Talalay’s willingness to push the limits of the technology available to her. In an era where these effects still weren’t commonplace, it’s remarkable to see them at work on a relatively low-budget slasher movie. Given Talalay’s background in mathematics and computer programming (after graduating from Yale, she had an eye on furthering her education until she landed a job working with John Waters—talk about career arc goals!), it’s no surprise that her three ’90s features consistently explored the multimedia possibilities at the disposal of filmmakers. Between the VR sequence here, the 16-bit Freddy mayhem in FREDDY’S DEAD, and the animated interludes in TANK GIRL, you see the hallmarks of an imaginative filmmaker looking to expand the medium’s boundaries with idiosyncratic bursts.

GHOST IN THE MACHINE in particular is not without its flaws: its slasher could use a little bit more personality, it could use another standout splatter sequence or two, and its thin plot hinges on a gimmick that feels a little bit derivative (ironically enough, this movie conjures up ghosts of SHOCKER, another attempt at chasing Freddy Krueger). But this is also something we’ve said about so many other slasher movies over the years before bestowing them with a cult classic status.

I can’t boldly proclaim that this is the future for GHOST IN THE MACHINE; however, I do think it’s worthy of a nice Blu-ray release that would give everyone an excuse to give it another shot—especially now that ’90s nostalgia compels us to wistfully recall a time when toxic assholes on the internet was just the stuff of harmless fantasy.

Tags: 1993, Brandon Quintin Adams, Chris Mulkey, Ghost In The Machine, Internet, Jessica Walter, Karen Allen, Rachel Talalay, Shevonne Durkin, slasher, Ted Marcoux, Virtual Reality, Wil Horneff

No Comments