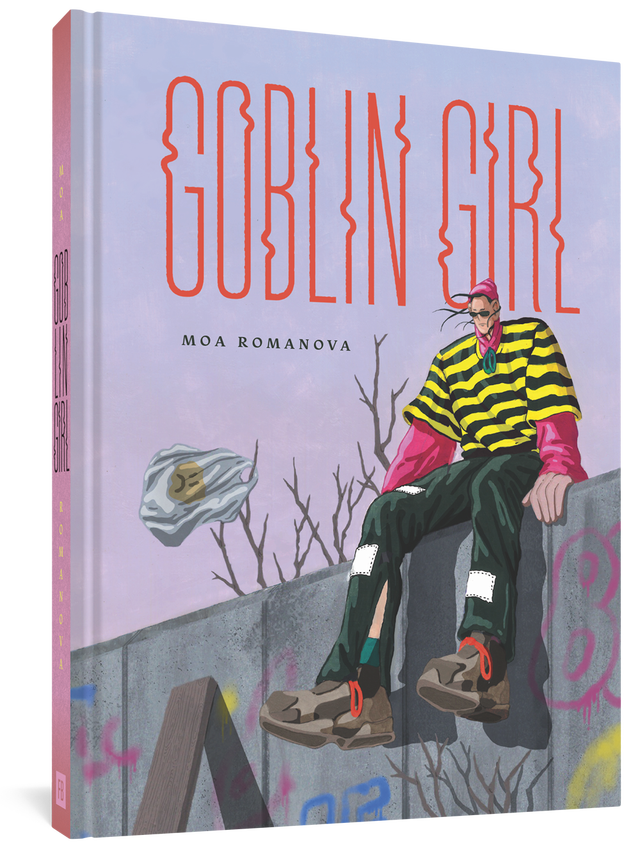

Hailing as she does from Stockholm, Sweden, Moa Romanova’s name isn’t one that is particularly well-known here in the US — but I have a distinct feeling that her Fantagraphics-published debut graphic novel, Goblin Girl, is going to change all that in a hurry. Toeing a tightrope-line between pure autobio and fictionalized faux-memoir, with the distinction between which “parts” of the book are which never being explicitly delineated, this is a seamless and powerful work that navigates the always-choppy waters of mental illness with raw honesty, emotion, and a sense of authenticity so profound that it almost doesn’t even matter how much of it is derived from Romanova’s daily life or not.

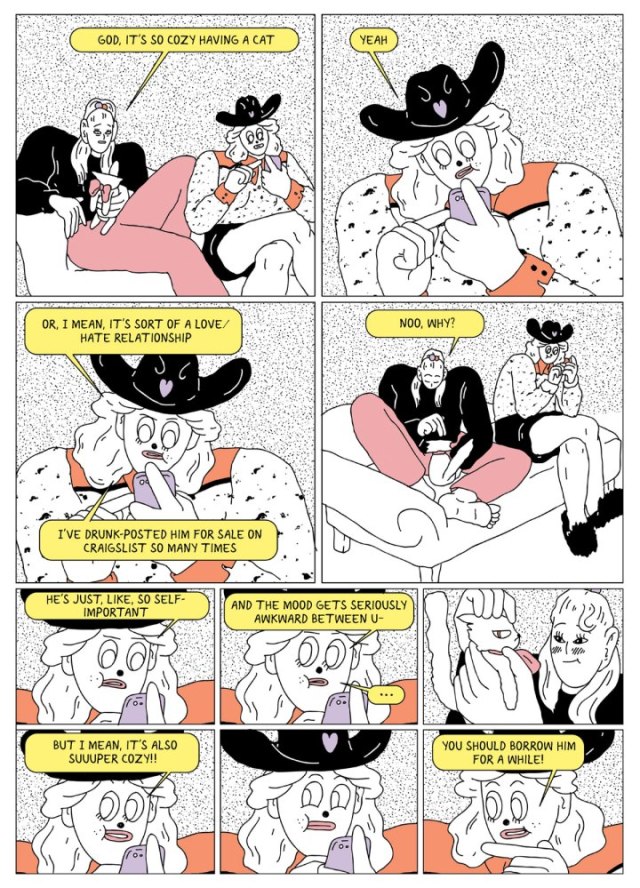

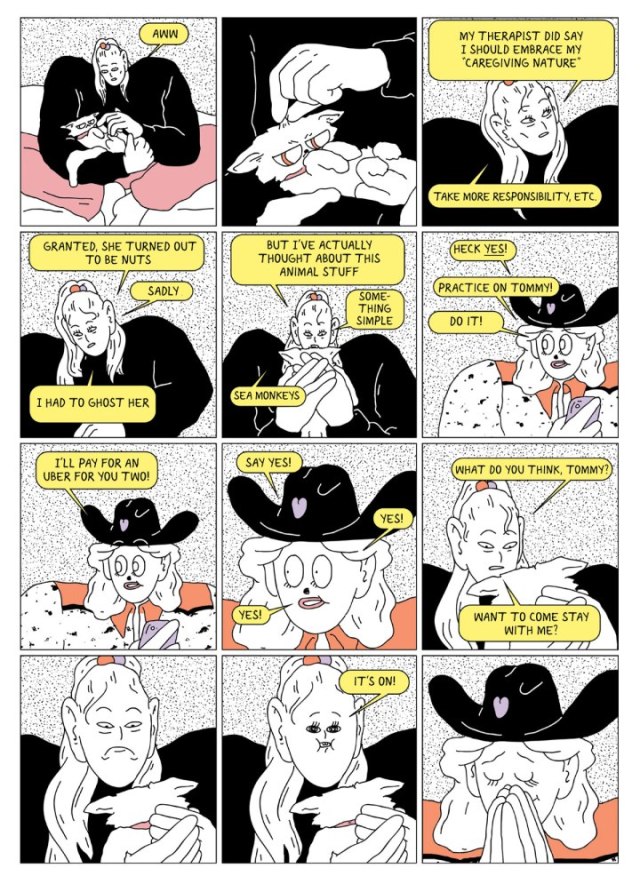

That being said, she’s still clearly finding her voice as a cartoonist, at least on the artistic side of the ledger: Her panel layouts, lettering, backgrounds, color choices, and caricature-ish flourishes owe a lot to Michael DeForge, while her less-specific and physically distinctive portrayal of her self/stand-in falls somewhere along a stylistic continuum between Eleanor Davis‘ early works and Tommi Parrish‘s fluid abstraction. This isn’t a criticism per se — if you’re gonna borrow, borrow from the best — but it stands out to me as the one area where Romanova could stand to differentiate herself from her influences a bit, so I’m getting it out of the way early.

Now for the gushing, and well-deserved, praise.

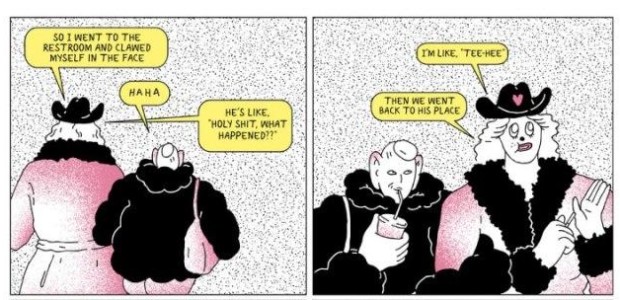

While we’ve seen the thematic territory Romanova mines here far too many times to count, we’ve seldom seen it communicated with this level of frankly disarming candor. So many cartoonists who choose to shine a light on mental health struggles — be they someone else’s or their own — understandably enough go for the straight sympathetic portrayal or, when they opt for something different, downplay it all through self-deprecation that’s ultimately designed to elicit the same sympathetic result. Now, to be perfectly clear: Even I’m not a big enough asshole to say that people who suffer from the symptoms Romanova does herein — depression, panic attacks, withdrawal, emotionally self-destructive relationship choices — aren’t absolutely deserving of all the sympathy in the world, but it takes a very deft narrative touch to avoid the pitfalls of either asking for said sympathy openly or “tricking” readers into feeling it by doing the whole “Oh gosh I suck, don’t shed a tear for me because I’m just a pathetic waste of time” shtick. What takes a lot more skill is to maintain a first-person point of view and illustrate every up and down with passion and pain and confusion and distress and promise and poignancy, but to do so without resorting, either by default or design, to anything that could be remotely considered manipulative. This takes a ton of confidence, and even if Romanova may not seem especially confident throughout much of this book, trust me when I say that when it comes to laying out her truth on paper via her art, she absolutely is.

Nowhere does her doppleganger-at-the-very-least protagonist seem less confident, or even particularly smart, than in her interactions with a much older man she meets online (by contrast, she’s pretty firm in her constant belief that her therapist is a full-of-shit huckster, even though she keeps on going to her appointments), known only as “Known-TV-Guy, 53” — who, for his part, doesn’t make things in that regard very easy for Romanova by toying with her emotions (one minute he claims he loves her, the next he only meant that he loves her art and wants to support her development) almost as some kind of bizarrely reflexive (or at least passive-aggressive) from of misogyny, but I do feel like the book’s back-cover promotional blurb oversells his centrality to the proceedings: He reappears at crucial times, but he’s hardly a constant, and he’s best viewed almost as a cipher via which we can can gauge our heroine/author’s own health, happiness, and judgment via her decision-making in regards to what passes for their “relationship.” I get that you’ve gotta sell some sizzle along with the steak, but readers shouldn’t go into this thinking it’s some low-key Fatal Attraction, even if Romanova does become overly fixated on him for a time. The role he serves in the story is absolutely vital, but it’s not, as the young people say, “All that.”

The book itself, however, most assuredly is. Yeah, you’ve read comics that tread this same path, but Moa Romanova makes it all fresh, new, and interesting again by maintaining a self-assured voice and viewpoint throughout, made all the more remarkable by the fact that a distinct lack of self-assurance is kinda what it’s all about. Goblin Girl came out relatively early in 2020, but I have a distinct feeling it’ll be there again at the end of the year when all of us critics are putting together our various “best-of” lists.

Tags: Columns, Comic Books, Comics, Fantagraphics, Melissa Bowers, Moa Romanova, Stockholm, Sweden

No Comments