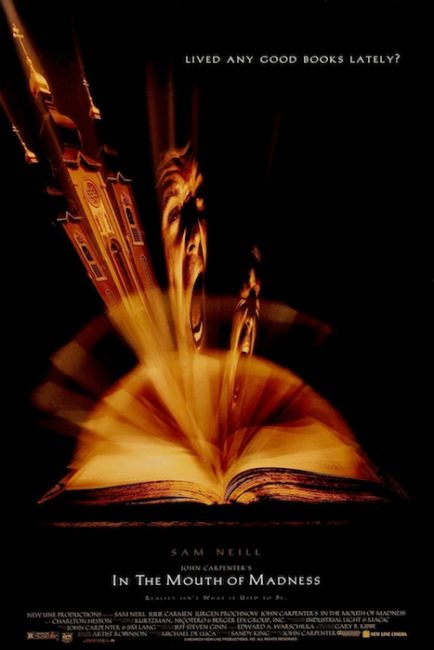

John Carpenter’s IN THE MOUTH OF MADNESS was released on February 3, 1995. To celebrate its 25th anniversary, Matt Wedge sings its praises as the best H.P. Lovecraft film adaptation ever made by not directly adapting any of the trailblazing writer’s work.

I am going to say something here that will not win me many friends in horror fandom. Actually, it might cost me some of the few friends I already have in this niche corner of pop culture.

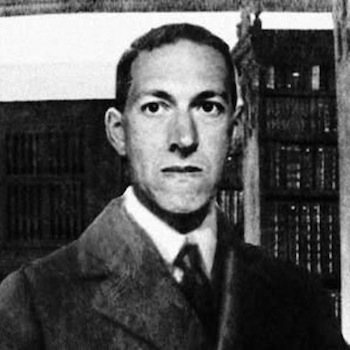

I do not think H.P. Lovecraft was a good writer.

Let me clarify this statement. I think Lovecraft was exceptionally imaginative. You have to be to construct something as weirdly intricate and downright confusing as his Cthulhu Mythos. I also think he was very in tune with the deepest unconscious fears of humans in the way he would return time and again to the kind of cosmic horror that the mind can scarcely grasp. Clearly, he was a man with something to say. I just think he was a lousy writer.

Please allow me to further clarify. My issues with Lovecraft’s writing do not come down to his archaic, near-impenetrable prose nor the ugly racism and misogyny in his personal life that leaked into his work (although those definitely do not help). My issues with his writings boil down to the fact that he did not write actual stories. To be charitable and read his work as tone poems instead of narratives even does not hold up since his prose was florid and ridiculous in ways that would make a good editor sag in their chair in defeat. Simply put, I believe Lovecraft was a terrific idea man, but that does not necessarily equate to great writing.

I promise, I am eventually going to tie this into IN THE MOUTH OF MADNESS. I just ask for your patience.

The film industry loves idea people. Even better, they love idea people whose ideas are in the public domain. In the late ’60s through the ’70s, horror producers started cranking out Lovecraft adaptations both direct (THE DUNWICH HORROR, THE HAUNTED PALACE) and as homage (Fulci’s CITY OF THE LIVING DEAD and THE HOUSE BY THE CEMETERY). But it wasn’t until 1985, when Stuart Gordon adapted the then little-known (outside of Lovecraft academic circles; amusingly, it was well-known by scholars of his work as his worst story) Herbert West—Reanimator and gleefully skewered the hysterical sexual repression in most of Lovecraft’s work (and reputedly, his personal life) by turning it into a gonzo splatter flick full of the type of graphic violence and sex that would have driven the author mad, that filmmakers really sat up and took notice.

After RE-ANIMATOR caught lightning in a bottle, it became routine for films to pop up claiming to either be based directly on a Lovecraft work or be “Lovecraftian” in their intent. In these films, slimy monsters with tentacles, talk of “old gods” or “the old ones,” and long-forgotten words like “stygian” and “eldritch” were used as shorthand to tell the audience they were in “Lovecraft territory.”

In all honesty, I like several of these films. Like I said, I see Lovecraft as a great idea man, so when good filmmakers like Gordon, Sam Raimi, Tobe Hooper, and John Carpenter took inspiration from the groundwork he placed down, the results could be truly special.

Carpenter’s loose “Apocalypse Trilogy” that began with THE THING and continued with PRINCE OF DARKNESS was wrapped up with IN THE MOUTH OF MADNESS. All three films had Lovecraftian elements (PRINCE OF DARKNESS actually feels like a lost Fulci film in the vein of his Lovecraft-inspired works) but it was IN THE MOUTH OF MADNESS that really embraced all of the traditional elements of a Lovecraft-inspired movie. And here is where I drop my second and third potentially controversial opinions in this piece.

I believe that IN THE MOUTH OF MADNESS is John Carpenter’s best film and is also the best film either adapted from or inspired by Lovecraft’s works.

In many ways, IN THE MOUTH OF MADNESS fits into Carpenter’s usual brand of filmmaking. It is efficient in setting up its characters and main premise. It makes great use of negative space to create suspense and dread. The protagonist is a charismatic cynic who claims to only care about himself, but seems to nurse a wounded idealism deep down inside that still nags at him from time to time.

But while there are some similarities to his older films, it feels very little like any of Carpenter’s other works. You can even sense him trying hard to establish a tone outside of what viewers expect from him with the opening hard rock theme (co-written by Carpenter and Jim Lang) that is unlike any other in his filmography to that point.

Curiously, even though the title of the film sounds like a lost Lovecraft tale found in the attic of an old house in Providence, the first act plays out like Carpenter doing a comic book movie adaptation of a Stephen King story. The opening, set in an asylum as John Trent (Sam Neill) is greeted by a weirdly cheerful clinic director (John Glover) and interrogated by a solemn official with an unknown organization (David Warner), is full of absurd humor from the clothing choices to the dialogue (“I’m sorry about the balls! It was a lucky shot, that’s all!) to the use of a Carpenters song to quiet down the agitated patients. While Carpenter was never a stranger to comedy in his films before production began here, his humor tended toward the deadpan and satirical. The opening of IN THE MOUTH OF MADNESS has more in common with the outlandish Hair segment of BODY BAGS and maybe a little bit of BIG TROUBLE IN LITTLE CHINA than anything else Carpenter had made up to that point.

But just as it seems like the film is going to settle into Carpenter taking the piss out of the type of supernatural horror he spent most of the ’80s making, it abruptly shifts into a noir-style detective story as insurance investigator Trent recalls his look into the disappearance of best-selling horror novelist Sutter Cane (Jürgen Prochnow). This section of the film doubles down on the noir sensibilities by introducing a femme fatale in the person of Styles (Julie Carmen, having fun vamping it up), Cane’s editor, who joins Trent on his trip to a small New England town where he cynically believes the writer has holed up as part of a promotional stunt cooked up by his publisher (Charlton Heston).

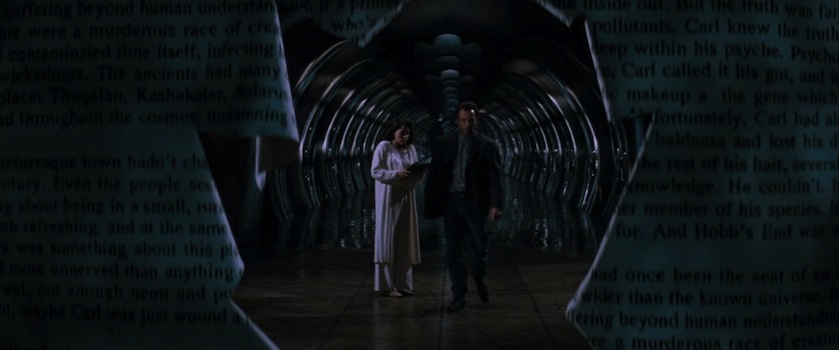

The introduction of Cane’s work pushes IN THE MOUTH OF MADNESS in a meta direction. Not only does Carpenter seem to be poking fun at his own ’80s output, but also at the mega-success of Stephen King by turning King into a reclusive oddball who is inspiring madness in his readers. While nearly everything about the film is played with a layer of comedy for the first thirty or so minutes (even the jump scares are done in a tongue-in-cheek way), once Trent and Styles arrive in the town of Hobb’s End, the film turns deadly serious and dives into territory that is decidedly Lovecraftian in the way it presents cosmic horror as the inability of people to escape the fate that an uncaring Universe has imposed upon them.

What Carpenter does here that few other filmmakers have done when tackling direct or indirect Lovecraft adaptations is to focus less on the slimy, tentacled monsters (although that aspect is present here in small doses) and more on the madness that cosmic horror inspires. By the end of the IN THE MOUTH OF MADNESS, it’s not only consummate disbeliever Trent who has been driven insane by supernatural forces beyond his understanding, but the entire world.

The overtly funny opening thirty minutes of IN THE MOUTH OF MADNESS actually does an impressive job of operating as audience misdirection. Despite his reputation as a master of horror, Carpenter’s film work has been very much a cross-pollination of genres. He directed only three truly balls-to-the-wall horror films (HALLOWEEN, THE THING, PRINCE OF DARKNESS) before he tackled IN THE MOUTH OF MADNESS. It is understandable then that audiences might have taken the goofy comedy moments at the beginning of the film to be the tone they were going to get for the entire flick. Hell, during my first watch of the film, I was surprised when it jumped the rails from BIG TROUBLE IN LITTLE CHINA silliness and steered hard into Lovecraft territory.

Not only does the first act plus of the film work as misdirection, it also serves as a point of light comparison as the movie goes to some seriously dark places in its look at Lovecraftian cosmic horror. Old ladies turn into snake-like creatures and murder their husbands with axes. A man commits suicide because the narrative requires him to (“I have to. He wrote me this way.”). Hordes of sadistic children chase injured dogs across Church lawns. Even the climax, as Cane reveals himself to be less a horror writer and more of a prophet through which the dark things of the Universe express their cruel intentions, is dripping with Carpenter’s caustic belief that human beings will eventually hasten their own extinction.

There is a sense of paranoia and helplessness to IN THE MOUTH OF MADNESS that would probably draw a favorable reaction from Lovecraft. While the opening comedy bits are out of step with the old Puritan’s writings, Carpenter avoids turning the original screenplay by Michael De Luca into the usual sex and gore exercises of provocation that most filmmakers over the years have conjured up when referring to Lovecraftian horror. Carpenter is more interested in exploring the truly frightening idea of an uncaring Universe destroying life on Earth than he is in commenting on the sexual repression and implicit violence in Lovecraft’s work. In a very real way, Carpenter has managed to put together a more faithful Lovecraft adaptation than any other filmmaker before him. He was able to do this because he did not have to rely on the half-finished writings that come with Lovecraft’s name recognition.

Given its apocalyptic focus on a world intent on destroying itself, IN THE MOUTH OF MADNESS was out of place in February of 1995 when it was released to an America that was largely sliding by with few conflicts in relative economic prosperity. It could have fit in with Carpenter’s angry late-’80s output, but in all honesty, it feels more relevant now than any time since it was released. In an America that is incredibly divided and seems to have the potential to tilt over into full-blown anarchy at a moment’s notice, the film still feels timely. Not only does it find the heart of Lovecraft’s fear when it comes to the idea of looking into the abyss, it is filtered through Carpenter’s point of view that we should laugh in the face of the monsters and gods poised to emerge from that darkness. What else could be more human? What other choice do we have?

Tags: Charlton Heston, Cosmic Horror, David Warner, H.P. Lovecraft, in the mouth of madness, john carpenter, John Glover, Julie Carmen, Jürgen Prochnow, Michael De Luca, Sam Neill

No Comments