This is the eighth in a series of fifteen planned reviews of the films of John Flynn. During his 33-year career, Flynn directed everything from intimate character studies of volatile, potentially violent men to dark revenge films to early Steven Seagal vehicles and everything in between. Utilizing a spare style of filming that subscribed to the idea that the audience should not be aware of the director, Flynn placed an emphasis on strong performances and cleanly shot and edited action sequences that showcased impressive stunt work. His films show how a director with a clear vision can elevate even the most generic potboiler into a sturdy genre film worthy of rediscovery, yet most film buffs do not know his name.

In my look at John Flynn’s OUT FOR JUSTICE, an early Steven Seagal vehicle, I wrote the following:

Much like I have only interviews to perceive how Flynn was in his personal life, I only have his films to determine that he was a strong director who—no matter what—made movies his way. This is a determination that is fairly easy to make based on the consistency in vision from film to film. That is why OUT FOR JUSTICE felt like a cold bucket of water in the face. It is the first of Flynn’s films that I have watched where you could feel the producers — namely, Steven Seagal — pushing him around.

I cannot say that it necessarily feels like the producers of BRAINSCAN pushed Flynn around. The film moves quickly, with the kind of direct approach that Flynn favored in his career, but the material and tone feels strained, as though the film was rushed into production while the script was being revised on an hourly basis. The resulting hodgepodge of serial killer horror, sci-fi, early stabs at virtual reality, and teen dramedy is an absolute mess. It is an entertaining mess, overall—but a mess, nonetheless.

The opening-credits sequence offers up a nicely edited crosscut between sixteen-year-old Michael (Edward Furlong) having a nightmare and himself ten years earlier as he crawls on a broken leg to his mother who has just been killed in an automobile accident. With an eerie, propulsive score from George S. Clinton, moody lighting by cinematographer François Protat, and an escalating sense of tension, this opening sets up a high level that the film only occasionally comes close to living up to.

In the present day (here, the early ’90s), Michael lives in a pleasant suburb. He has a massive attic bedroom with a state-of-the-art (for the time) media center and a computer into which he has programmed a personality named “Igor.” Since he is played by Furlong in the early ’90s, Michael is clearly a troubled teen. Still haunted by the accident that killed his mother and left him with a pronounced limp, he sequesters himself in his bedroom, reading Fangoria and watching horror films. His only connection to the outside world is Kyle (Jamie Marsh), his equally unfit-for-high-school-society friend.

Michael and Kyle have the kind of awkward dialogue/relationship that too many adult screenwriters give to teenagers (their repeated sign off to conversations of “buddies forever” is particularly cringe-worthy), but Furlong and Marsh are good enough that they are able to convey a longtime friendship despite the artificiality.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for Michael’s pining puppy love for Kimberley (Amy Hargreaves), the girl next door. In a trope that I suppose was intended to show Michael’s pure longing for Kimberley but comes off as intensely creepy, he videotapes her in her bedroom from his window and re-watches the tapes, while chiding himself for being “sick.” It’s an unintended ugly moment in a movie that is largely a lark (despite a plot that hinges on a series of murders).

When he learns of an interactive CD-ROM game (remember, it’s the early ’90s) called “Brainscan” from an ad in an issue of Fangoria that promises bloody violence, Michael—ever the horror fiend—orders it without asking too many questions. Only, he does not ever actually order it. He calls the phone number to ask some questions, only to have the game foisted upon him when a disc arrives in the mail.

The game is supposed to be a virtual reality experience, but instead it induces a hypnotic state in Michael that causes him to dream in a first-person Giallo-style (complete with black gloves) experience as he stabs a man to death. Michael wakes up in his bedroom, amazed and energized by the experience. Then he discovers that the man he dreamed of murdering was actually killed. At that point, the film takes an ill-advised left turn.

That left turn comes in the form of a character named Trickster (T. Ryder Smith). A demonic force of some kind, he acts as the physical embodiment of the Brainscan game as he appears to Michael and explains that he now has to play the game three more times or risk being caught by the police or possibly killed…or something like that. It is hard to understand the rules and threats that Trickster lays down because everything is kept so vague.

Not only is the purpose of Trickster questionable within the plot, but also his outlandish appearance (think a demonic clown with facial piercings, teased hair, and black leather ensemble), use of bad puns and one-liners, and supernatural ability of avoiding injury are clearly intended to bring to mind Freddy Krueger. And I am here to tell you, dear readers, Trickster is no Freddy Krueger.

Forget for the moment that Trickster essentially serves no purpose in the film other than to explain the rules of the game to Michael. His presence in the film makes it feel as though Flynn and screenwriter Andrew Kevin Walker are out of step with the times. BRAINSCAN was released in 1994 (my guess is that it was filmed in 1993), three years after the end of the original run of NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET films and the same year that Wes Craven turned Freddy Krueger back into true nightmare fuel for WES CRAVEN’S NEW NIGHTMARE. If Trickster had been even a quarter of the screen presence of Freddy, his inclusion might be justified. Instead, he is simply an obnoxious intrusion to a film that does not need him.

But the efforts of Flynn and Walker to include Trickster in the film, come off as half-baked. They try to make him the devil on Michael’s shoulder, whispering in his ear all the bad things he should do. They try to make him comic relief, forcing in a scene where he is practically a Looney Tunes character making a mess of Michael’s room. They try to make him the true villain, pulling all the strings of the plot. None of these moments work because the film is set up to be about the damage that has been done to Michael’s soul by losing his mother at a young age and whether or not he will give in to the darkness that threatens to engulf him. Having an off-brand clown pop up every five or ten minutes sucks the air out of any tension or honest emotion that Furlong and Flynn work up in the more straightforward dramatic scenes.

Before the inclusion of Trickster, there were some clunky dialogue exchanges and bits of character building, but at least the film had a clear central dramatic question: is Michael just a troubled kid with a good heart or is he a budding sociopath? While he apparently did murder the first victim while under a hypnotic trance, the choice of whether or not he continues on with the game should be left up to him to work out on his own instead of being coerced into it by a third-rate knockoff of one of the most iconic horror villains of the ’80s. Trickster’s presence deflates everything the movie should be about.

It says a lot about Flynn’s ability as a craftsman that even with such a huge misstep as the inclusion of Trickster, BRAINSCAN still is very watchable. He gets pretty good performances out of the notoriously uneven Furlong, Hargreaves, and Marsh (heck, even Smith isn’t bad when giving Trickster some rare subtle touches), stages a great ten-minute suspense sequence as Michael tries to cover the tracks of his murder that leads to an ironic gut punch, and does incorporate some effective humor that does not involve Trickster.

The fact that there is a recognizably good movie trapped in between all the silliness in BRAINSCAN is what makes it so frustrating. While Walker is the credited screenwriter, I have to assume that there were uncredited writers changing the script as the film was being shot in an effort to chase trends like virtual reality, latchkey kids getting into crime, and excessive product placement (seriously, everyone in this movie has an Aerosmith poster on their wall and I wonder if Fangoria had to pay to get mentioned so many times in the first act) that were hot at the time (or, in the case of Trickster, five years earlier).

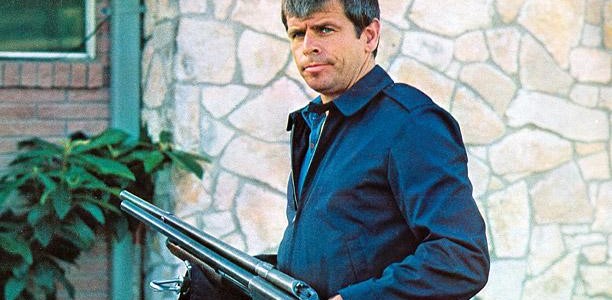

That feeling of the movie being changed on the fly keeps it from ever hitting the deeper emotional level it had the potential to reach. As the focus moves off Michael and on to Trickster and a homicide detective (Frank Langella, phoning it in) in the second act, you can feel the film slipping out of Flynn’s control.

That lack of control is a real surprise from Flynn. Even when working with a lesser script for a film like DEFIANCE, he still injected a consistent atmosphere and forward momentum. With BRAINSCAN, the suburban setting feels generic and most of the supporting characters lack any distinguishing characteristics (let alone actual depth) to make the audience feel any concern for them even when they could be next on the chopping block.

Perhaps, more than anything, the issue with BRAINSCAN is simply that Flynn was not a horror director. With the exception of the giallo-inspired murder sequence, he handles the film like more of coming-of-age drama about a troubled teen with some dark undertones. Given that the scenes that serve that purpose work well, it is a shame that so much effort was put into burying that thread in favor of trying to establish a new horror villain in Trickster. I believe if the director is uncomfortable with the direction a film is going, the audience can feel it. I could feel intense discomfort in BRAINSCAN.

In my research into Flynn’s life and career, I have turned up very few interviews with him. BRAINSCAN was not mentioned in any of these interviews, so I did not bother researching the film before writing this piece. But I am intrigued enough by what works in the movie that I can see it nagging at the back of my mind for weeks to come until I go down the rabbit hole of piecing together where things went off the rails. I suppose that interest in understanding what went wrong is a better reaction to have than just allowing the movie to disappear from my memory altogether. That is not a recommendation to watch the film; simply an acknowledgement that it had potential that continues to bubble up to the surface, despite several major missteps. There are worse things that could be said of most movies. But there are also much better things that could be said of a film directed by someone as talented as John Flynn.

Catch up on previous episodes of our John Flynn retrospective!

Tags: A Nightmare on Elm Street, Aerosmith, Amy Hargreaves, Andrew Kevin Walker, Brainscan, Defiance, Edward Furlong, Fangoria, Francois Protat, Frank Langella, Freddy Krueger, George S. Clinton, Jamie Marsh, john flynn, Out for Justice, steven seagal, T. Ryder Smith, Wes Craven, Wes Craven's New Nightmare

No Comments