Shameless exploitation of a beloved (or even just well-known) property is just something we’ve come to wearily accept with modern filmmaking. Even if it requires a bit of reaching to make the most tenuous of connections (I’m looking in the general direction of the recently-announced Clarice Starling CBS TV series that won’t involve Hannibal Lecter or SILENCE OF THE LAMBS), Hollywood is going to find a way to capitalize on familiar titles. And while it seems especially rampant these days, it’s an impulse that stretches all the way back to film’s infancy, when classic stories were told, retold, or “re-imagined” often within the space of mere months or years. Go watch 1942’s THE GHOST OF FRANKENSTEIN and tell me what it really has to do with the 1931 original, much less Mary Shelley’s novel. It happens.

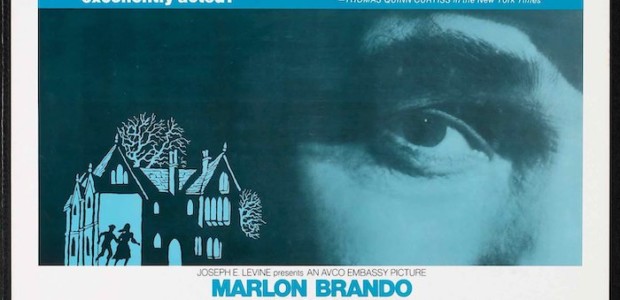

One of the more curious cases of this phenomenon came in 1971, a decade removed from THE INNOCENTS—which still stands as the definitive adaptation of Henry James’s The Turn Of The Screw. Sensing, perhaps, that audiences didn’t need yet another pass at James’s quietly haunting novella, AVCO Embassy and Michael Winner proposed something else: a prequel that explains how this ghost story became a ghost story in the first place by dwelling on the half-whispered lore to the original tale. In doing so, THE NIGHTCOMERS twists James’s ambiguous, ephemeral text into a sweaty, corporeal vision of sadomasochistic lust and warped childhoods, brining James’s repressed, perverse subtext surfaces to the text here in a story that, for all intents and purposes, is just a rendition of The Turn Of The Screw.

In this case, though, audiences don’t have a new governess serving as a surrogate and entry point into the bizarre domestic scene at the Bly house nestled in the English countryside. Rather, we find ourselves plunged headlong into it, as the house’s master (Harry Andrews) leaves recently-orphaned Flora and Mils (Verna Harvey & Christopher Ellis) in the care of housekeeper Mrs. Grose (Thora Hird), governess Miss Jessel (Stephanie Beacham), and gardener Peter Quint (Marlon Brando). Unaware of their parents’ untimely demise, the two siblings frolic about the fields and the house in a state of childhood bliss. A darkness looms, however, particularly in the unsettling fascination the children have with Quint, a firebrand atheist who minces no words when it comes to explaining the ways of the world to the increasingly forlorn brother and sister.

Because it’s essentially filling in what should be familiar backstory, THE NIGHTCOMERS is a thinly-plotted slow burn, one that relies on an inherent sensation of fatalistic doom, so long as one is familiar with James’s novella. Without the novella’s ambiguous supernatural elements, this prequel still feels like a gothic doppelgänger of sorts since Winner casts the it in an ethereal haze, emphasizing the dreary desolation of this rustic tableau. It’s filled with gradually unsettling imagery, like Quint giving a frog a cigar and causing it to explode right in front of the morbidly curious children, an act that doubles as a prelude for the further twisted sights the siblings will witness.

Most of these sights are of a sexual nature, as Flora and Miles (here reimagined as something closer to adolescents, though it’s really no less creepy) attempt to understand and reckon with the relationship they know exists between Jessel and Quint. Knowing nothing of romantic love and even less about sex, their perceptions become especially warped when Miles spies on the adults’ sadomasochistic escapades in a truly galling scene that foreshadows the sort of outlandish sleaze that would make both AVCO and Winner infamous in the coming decades. I hesitate to call it the “stand-out scene” in THE NIGHTCOMERS because it involves a child watching two adults engage in wild, sweaty, and weird sex acts; however, when you put it that way, it’s hard to consider it anything but a deranged moment couched within an otherwise stuffy period drama.

Things grow even more perverse when Miles tries out some of these acts on his own sister, whom he hog-ties to the floor to the aghast horror of Mrs. Grose. They’re just “doing sex,” he insists, before the two children run off like a couple of imps in a scene that hints at the wild, untamed psychosexual drama you might expect from the parties involved, but THE NIGHTCOMERS doesn’t exactly dwell on such schlock. Despite these uncomfortably squeamish bursts, the film mostly aims to be a delicately tragic (albeit disturbing) tale of the children’s misguided quest to keep Jessel and Quint together—by any means necessary, as it turns out.

Brando looms largest here, naturally. Released just before the actor would see a resurgence in popularity thanks to THE GODFATHER, THE NIGHTCOMERS may have embodied the sort of films that many felt were beneath the iconic performer during this period. You’d never know it from his turn here, though. Despite an unruly Irish accent that varies throughout the film, his take on Quint is quite magnetic, if not downright hypnotic at times. It’s easy to see how these children would be held under the sway of his bombastic, devil-may-care personality, especially when he clashes with the prudes in their lives.

Speaking of which, Quint’s relationship with Jessel proves to be the film’s most compelling lynchpin. What starts as an apparently non-consensual tryst (Quint comes to her bed in the night and gropes her, and a later exchange suggests he was uninvited) grows into a secret, lusty affair that Jessel can’t quit. Her verbalized repulsion for Quint is matched only by her fascination with him and the pleasures of the flesh. This, I think, is what THE NIGHTCOMERS ought to really be about, especially since Beacham is clearly up to the task of projecting vulnerability, curiosity, and Victorian disgust all at once. Couching the story form her point of view and foregrounding her descent into a mad, almost inexplicable lust would make for an intriguing companion to James’s text. After all, it’s that repressed sexuality simmering just below the surface of The Turn Of The Screw that makes it a definitive Victorian-era dispatch, so THE NIGHTCOMERS is not out-of-bounds in exploring this.

However, it must be said that Winner and company weren’t quite interested in exploring it thoroughly. THE NIGHTCOMERS is ultimately more concerned with connecting its surface-level dots back to the original story, which demands the sacrifice of its doomed lovers. Once this plot thread comes into focus, THE NIGHTCOMERS emerges as an admittedly melancholy riff on the creepy kid routine that would become more commonplace as the 70s rolled along. Winner embraces the horrific implications of the story here by forging the Bly house into a gothic crucible of forlorn landscapes and violent outbursts at the hands of the children. Their impulsive reign of terror is as heartbreaking as it is horrific, as their pure motivations produce the couple of gnarled, ghastly corpses this story demands.

It makes for the rare prequel that would work regardless of the audience’s familiarity with The Turn Of The Screw. The uninitiated might find THE NIGHTCOMERS to be a shocking, twisted tale of two strange siblings’ descent into a sort of innocent psychosis, for lack of a better term; others should find that it gives the novella a tragic heft in the way it humanizes the two spirits that will later come to haunt the Bly grounds. Of course, the latter might also argue that The Turn Of The Screw doesn’t need such heft since its meant to float on a phantasmagoric air of uncertainty, which brings us back to square one: is THE NIGHTCOMERS just an exploitative cash-grab that isn’t even necessary?

Perhaps it might be fair to say it’s more interesting than it is vital, existing in a space where it’s more of a cult curiosity by default. I mean, can you imagine hearing that there’s a Marlon Brando-led prequel to The Turn Of The Screw directed by Michael Winner and not wanting to see it? Therein lies your answer to whether or not THE NIGHTCOMERS is completely necessary. Sometimes, these things just speak for themselves—even when they really don’t have much to say beyond their shameless exploitation.

[This post published in anticipation of THE TURNING, the latest adaptation of James’s The Turn Of The Screw, which is in theaters this Friday, January 24, 2020]

Tags: Avco Embassy, Christopher Ellis, Harry Andrews, Henry James, Marlon Brando, Michael Winner, Stephanie Beacham, The Innocents, The Nightcomers, The Turn Of The Screw, Thora Hird, Verna Harvey

No Comments