Historically I have despised the term “life-affirming,” particularly as it’s deployed most frequently in film reviews. It’s too frequently used to sell us honky horseshit like GREEN BOOK, stuff you generally know to avoid just by noting who’s calling it “life-affirming.” The idea is that these are movies that remind us of what is good in life, and worth fighting for, and surely that’s a noble purpose in theory but often “life-affirming” movies turn out to be soft-focus, middle-of-the-road, Oscar-hungry, weepy, treacly, ego-trip-y showcases that hit the broadest notes possible, lack any nuance anywhere, and arrive at the simplest conclusions. And the most irritating element, to me anyway, about calling a movie “life-affirming” is the obvious question: What’s the alternative? “Death-affirming?”

Well… yeah.

On October 21st, 2016, Leonard Cohen released an album and a title song called “You Want It Darker.” Sixteen days later, the United States of America managed to elect a fascist. The day after that, Leonard Cohen died. Guy knew something. For my part, on March 1st of that year, I lost my brother, my soulmate, the only person on Earth who has really ever had the power to pull me out of the bad black. And then things got worse. You want it darker?

Yes, I do believe that movies can be noble, that they can remind us of what’s good and what we need to fight for, but no, in times of greatest need I do not turn my desperate eye to honky horseshit. I turn to horror.

Horror movies can show us the worst of what humanity is capable of being. (I’m talking about fictional stories; documentaries can be set aside for the purposes of this conversation. THE ACT OF KILLING shows depths of depravity that THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE can’t ever reach, but knowing a story is fictional or fictionalized gives it an element of remove and makes it easier to ponder and to revisit, which is why I’ve seen one of those aforementioned movies once and the other about two dozen times.)

Horror shows us what truly evil acts our fellow human beings are able to conceive and execute. Horror shows us an unhappy truth: That sometimes the best of us don’t make it. That the good guys don’t always win. That in fact, it’s sort of rare. Horror shows us that at the very moment where everything appears to be at its darkest, that things can get even worse.

But horror also shows us how to get through. Horror shows us how to fight back against the darkness inside others and inside ourselves. Horror reminds us to keep fighting, even when the fight is ultimately hopeless. Not one of us will get off this planet alive — horror is the only genre that fully embraces this fact, even celebrates it. Horror is defiance. Horror is resistance. Even as death surrounds, even as we all know, whether in the back of our minds or right in front of our faces, that death awaits, horror is survival.

To that end, I asked our friends and contributors,

What’s the most life-affirming moment from any horror movie to you? When things get darkest, which moment from which horror movie do you turn to?

If you follow me on Twitter — and granted, not many people do — this comes as no surprise.

Today I was thinking about this moment again. I think about it a lot because I live in this moment, almost daily. You know this movie, so you know what he’s thinking here. And so you know what I mean. pic.twitter.com/XBQfJwA2ix

— Haunted Jon Abrams (@JonZilla___) September 12, 2020

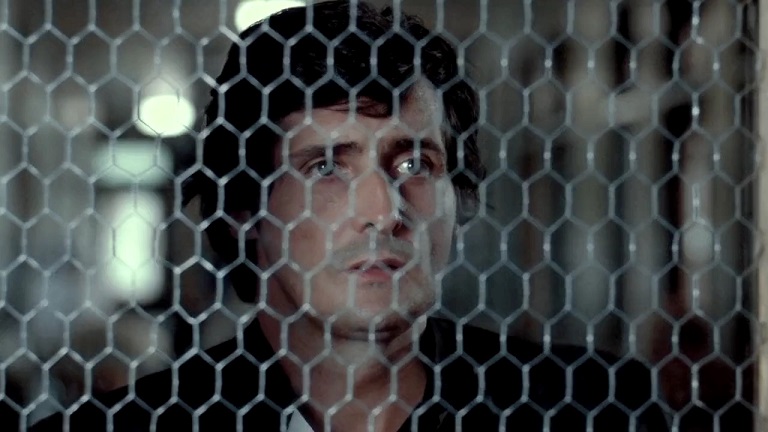

By the last moments of DAWN OF THE DEAD (1978), Peter Washington (Ken Foree) has had it. Having survived the zombie apocalypse this long, seeing his idyllic megamall fortress turn into a living tomb and finally having seen it overrun by the living dead due to a combination of greed, carelessness, and idiocy on the part of his fellow living humans, Peter knows it’s time to leave the mall, one way or another. The helicopter is gassed up on the roof. Fran Parker (Gaylen Ross), pregnant and dead-set on moving forward, considers the ladder to the roof. She turns to Peter, pleadingly, but he tells her to go ahead, saying in one of the most sincerely-delivered and believable-and-relatable-to-me line readings in all of American film history, “I don’t want to go. I really don’t.”

Fran doesn’t want to go it alone and she doesn’t want to leave her friend behind, but she is living for two now and has no choice but to proceed. Peter is resolute, unshakable, and Fran knows him well enough by now to now it. And besides, in the next moment, Steven “Flyboy” Andrews (David Emge), the father of her child, bursts through the door, fully turned. Peter ends Flyboy’s afterlife with a shot to the head, and it’s clear to Fran there’s no future here. So she heads to the helicopter.

Ghouls file into the room, slowly but definitively. Peter puts down his rifle and goes to a back room. The zombies fill the main room, many climbing to the roof, one with the rifle Peter surrendered. Peter sits down and takes out an antique Derringer, placing it against his temple. The first zombie to slap the door open has a huge Afro. Outside, dawn is breaking. Having seen one of the zombies emerge with Peter’s rifle, Fran figures she can’t wait anymore and gets into the cockpit. But below, Peter moves the gun from his own head and shoots that first zombie.

He punches his way out of the room, grabs a new gun, and knocks zombies aside left and right, scaling the ladder to the roof and continuing to juggernaut his way through the hordes between him and the helicopter, which is starting to take off. The musical cue is arguably the corniest in the film, a sort of John Philip Sousa triumphant score, but I’m fine with that and I hope you are too. One zombie gets Peter’s gun, but still Peter keeps moving, grabbing hold of the skids and climbing aboard the helicopter. Peter allows himself a sigh and then asks Fran, “How much fuel do we have?” She replies, “Not much.” He smiles a little and says, “All right.” Fran pilots them away from the mall’s roof and into a very uncertain beyond.

Of course, this movie wasn’t supposed to end this way. George A. Romero’s original plan was to allow Peter to go through with it. Fran doesn’t make it either. Not even the helicopter makes it. I firmly believe this was the better way to go. Not because I’m overly sentimental (although I do love those characters and performances), but because Romero in 1968’s NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD had already done the tragic and ironic death of his Black hero, to tremendous effect. Romero has been famously wry about the casting of Duane Jones, suggesting he played Ben only because he was the best actor for the job (obviously true) and not because he was Black. However, by 1978, Romero couldn’t have been believably naïve if he said the same of casting Ken Foree, although Ken was obviously the best actor for that job. But Peter is without question written to be Black. DAWN OF THE DEAD isn’t implicitly about race, but there are potent overtones. Peter is introduced, along with his soon friend Roger DiMarco (Scott H. Reiniger), in their former lives as SWAT officers, assigned to storm a housing project where the residents are mainly Black and Brown, and being overrun by zombies. I don’t have the space here (and it’s surely not my place) to fully get into it, but I have to imagine that a Black police officer in 1978 being ordered to use force against fellow Black people might wear on even a consummate professional like Peter. It’s a theme more relevant than ever today. And note how the first zombie that Peter shoots when he has his change of heart is Black (or was). There’s stuff going on here that is quintessentially American, and worth thinking hard about.

Clearly, I will never know what it’s like to be Black in America. But I do know what it’s like to love my Black friends and family, as much as I love myself — more. I know the rules are different for them than for me. I can’t accept that, though I don’t always know what to do about it. But I do know I want only good for them. Those are the eyes with which I come to DAWN OF THE DEAD. The character I’ve been drawn to most in this film, from my first viewing to the hundredth, has been Peter. It could be that Ken Foree is such a strong and steady presence, cooler when the other three roles run hot. It could be that Peter is just plain the coolest character (he’s the one who gets to say “When there’s no more room in Hell, the dead will walk the Earth.”) It could be that he resembles my best friend a little (he does). For whatever reason, I have tremendous affinity for this character, even identification with him, nowhere more than in that last moment.

I know what it’s like to be just-plain-done. I know what it’s like to not want to be here anymore. And I know that still I have to pick myself up and keep going all the same. There’s no quitting for Peter, and there’ll be none for me.

On the Daily Grindhouse Podcast, while remembering George A. Romero a year after my brother died, I said that this isn’t just a movie I love and learn from and could watch any day of the week. This is a movie I need in my life. This is a movie that reminds me to stand back up and fight my way to that helicopter, every morning of every day, until the gas runs out.

When I think about moments in horror that really reassure me, these life-affirming moments, my mind immediately is one specific scene in the original CARRIE (cliché, I know). In what I thought was an uncanny way, it paralleled a situation that happened to me in middle school, when I spent my days eating lunch alone at a table by myself and was at the precipice of puberty. The scene in question is the one where Tommy asks Carrie to prom, and she thinks it’s a joke — a prank, if you will. Now, we were not going to prom in middle school, so this isn’t an exact replica, but, well, you’ll see. One day I was walking to the back of the cafeteria to throw my trash out, and at the back of the cafeteria was the “popular boys” table. One of them stops me and asks me on a date. Instant red flags — nobody was into me; I was awkward and wore glasses and played the saxophone. So, I say no. Then another one asks. Again, no. And another. Lunch ends and we move onto classes. Throughout the rest of the day popular boys asked me out one by one, in what I was sure was a prank. I did not want to say yes and see what kind of pigs’ blood situation would play out. When I saw CARRIE, I immediately recognized this scene from my lived experiences, and it made me feel a lot less alone. It reassured me that I wasn’t the only one being bullied in such a bizarre and specific way. Conversely, it confirmed my fears that their intentions were not pure, and that something so horrific as what happened to Carrie could have happened to me. Ever since then, I’ve heard countless stories of similar situations. You’re never alone.

ROB DEAN:

Final Showdown in BUBBA HO-TEP (2002)

Written and directed by Don Coscarelli, based on a short story by Joe R. Lansdale, BUBBA HO-TEP finds Elvis (Bruce Campbell) and Jack (Ossie Davis) as elderly men in a retirement home that is beset by a soul-sucking mummy. Both men are already dismissed for being old, let alone the fact that they may have dementia or severe mental health issues since they sincerely believe they are Elvis Presley and JFK, trapped and forgotten in an assisted living facility. They are brittle, in pain, weak, tired… they are old.

Watching them stumble down the hall towards battling this Egyptian ghoul is a rousing moment. But it’s a life-affirming moment because they are doing all of this… and no one will know. No one will buy that the two possibly demented old kooks fought a mythical creature. Win or lose, the outcome for this pair is the same, a forgotten death and a life lost in time, mourned by none. Even if they win, it’s an anonymous victory because who will believe they were capable of defeating an ancient evil or that an ancient evil was preying on these geriatrics?

Despite the math pointing out why it’s a bad idea that can only lead to pain and the realization that, no matter what happens, they will be seen as crazy and slip away from the minds of a few people with each passing day. All of those reasons why it shouldn’t be done — and maybe can’t be done — doesn’t deter them. It’s done because someone has to do it. It’s done because you can’t wait for someone to fix it or assume “they” will take care of it. It’s done not because a win is guaranteed or they’ll be rewarded for it.

The Good fight isn’t fought because you’ll win — the Good fight is fought because it’s Good. No matter what hole people find themselves in, no matter how abandoned they feel, no matter what circumstances in their lives reduce their capabilities — they can still make a difference; they can still do Good. The world needs us in ways we don’t know (and may never know). We can’t forget how much power we still have within us.

The Monster Meets the Blind Hermit

THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN (1935)

“Alone, bad. Friend, GOOD!”

Perhaps us advanced, Twitter-fied Uber-fiends think we’ve progressed past such pop psychology notions as Nature vs. Nurture, but there is no doubting that these simplicities in contrast make for great horror art. In fact, the real tragedy of The Monster in Frankenstein (the book and films) is that he could have been all right, if given the proper social nourishment. And nothing illustrates this better than when Boris Karloff meets the blind hermit in THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN.

The hermit (O.P. Heggie) senses him as a man, not as a creature. A first for The Monster, whose outward appearance (not character) typically provokes fear and disgust. Their interaction (and codependency) is a charming and sublime testament to the bonds of Man, if we could only see past our petty differences.

One of my favorite scenes in cinema history and a true love letter to all us freaks out there.

As I’ve written before, one of the most anticipated cinematic moments of my then-young life was the 1998 release of HALLOWEEN: H20. The studio-prestige approach to a slasher series that had by then descended to dubious levels and flirted with going direct to video, along with the involvement of Jamie Lee Curtis, was a major reason to celebrate the real return of Michael Myers. Though easily the best sequel at that time, these days, in the face of changing sensibilities and especially 2018’s far superior rebootquel, HALLOWEEN: H20 feels more like a mostly positive mixed bag. Regardless of its flaws, however, it easily contains one of the best sequences from the entire series.

After surviving several encounters with her long-lost brother, who finally found her hiding place after twenty years, Laurie Strode has a clear path to escape in front of her – there are no barriers, no hurdles to overcome. She’s no longer trapped in a closet or pounding on doors that will never open. She’s got an idling SUV, an open security gate, and her son, John (Josh Hartnett), is begging her to get back in the car and go. But for half her life, Laurie’s been running from her past and hiding behind a pseudonym as the headmistress of a private school in the shadowy hills of Northern California. Her life is in near-ruins; she’s an alcoholic who wakes up screaming in the morning and has an army of prescription drugs waiting in her medicine cabinet to help get her through. And she’s tired of this version of her life – enough that she’s going to make the conscious choice to stop running. In HALLOWEEN and HALLOWEEN II, every blow that Laurie lands against her attacker is reactionary and based on in-the-moment survival. This version of Laurie, however, goes on the offensive and willfully takes on the role as predator instead of prey. After sending John away, Laurie shuts the gate, smashes its controls, grabs a fire axe, and enters the game, bellowing her brother’s name as the camera takes a God’s eye view of the abandoned school grounds and composer John Ottman’s orchestral rendition of the HALLOWEEN theme floods the screen. In a concept further explored in 2018’s HALLOWEEN, this is the scene where Laurie refuses to be the victim any longer, and if there were such a thing as inescapable fate, as Samuels once wrote, then she’s going to do the impossible and deny that fate as the victim… even if she dies trying.

THE EXORCIST has been called many things since its release in 1973: horrifying, transgressive, blasphemous. Rarely, however, is it considered to be life-affirming, and for good reason: optimism is pretty low on the list of emotions one feels after enduring this battle with damnation. And yet, it’s hard not to feel a glimmer of it in Father Damian Karras’s noble sacrifice when he invites the demonic entity into his body and tumbles to his own death before it can cause further harm. Karras’s battle unfolds well before the climactic exorcism, as he spends much of the film paralyzed by a crisis of his own faith. Haunted by the death of his mother, he wrestles with himself until this crucial moment, when he decides that good must triumph over evil. In his original review of THE EXORCIST, Roger Ebert insisted the film carries “some small measure of dogged hope,” a line that I’ve never been able to shake since reading it. Ever since, THE EXORCIST hasn’t simply been an unsettling manifestation of pure evil; rather it’s one of the great spiritual films ever made, one that insists that, if the Devil exists, so too does God, and His grace emerges in that stunning, climactic confirmation of faith.

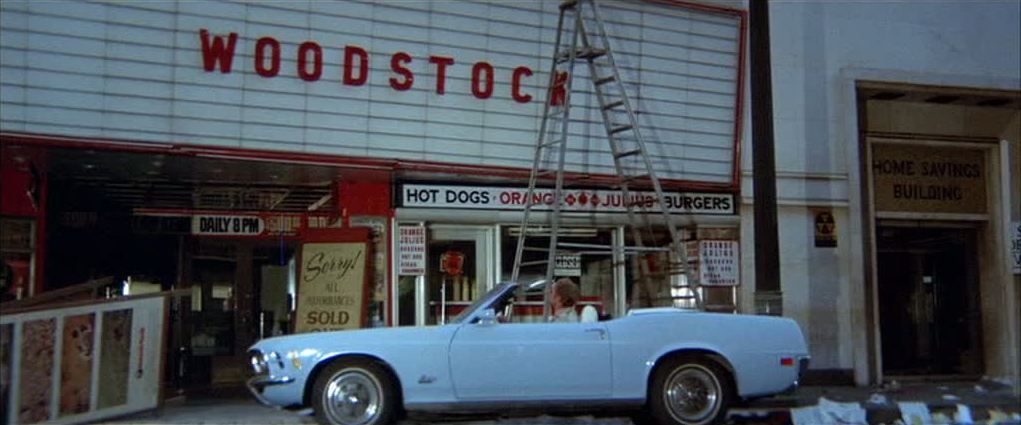

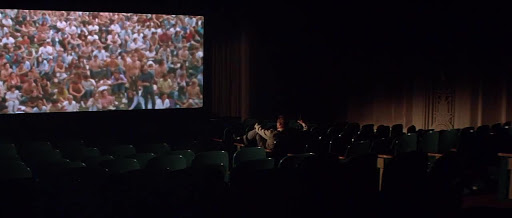

There’s a beautiful moment early on in THE OMEGA MAN (1971) when the film’s star, a middle-aged Charlton Heston, wanders into an empty movie theater in Los Angeles and sits down to watch WOODSTOCK (1970). We’ve become aware that the city he inhabits is seemingly empty of life due to a catastrophic event that has wiped out the population, and Heston’s character moves through the destruction in a methodical manner without emotion. This makes the film he chooses to watch a particularly odd choice. WOODSTOCK documents a three-day concert and historic counterculture moment largely attended by youth in 1969 eager to remake the world as a more loving place that embraces alternative lifestyles, decriminalizes drugs, and promotes peace. And as Heston watches the film while keeping a firm grip on a large gun he’s carrying, the macho, self-assured actor begins mouthing song lyrics and repeating conversations, which indicate he’s seen WOODSTOCK many times before. Despite the horrors happening outside, Heston’s character has returned to the cold dark comfort of the theater often to interact with the young people on screen, enjoy their music and memorize their message of peace. It’s a potent reminder of the power of cinema and how it can help us reconnect with the best aspects of our world during times of utter hopelessness and despair.

- [THE BIG QUESTION] WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE FEMALE ENSEMBLE IN MOVIES? - July 22, 2016

- [IN THEATERS NOW] THE BOY (2016) - January 24, 2016

- Cult Movie Mania Releases Lucio Fulci Limited Edition VHS Sets - January 5, 2016

Tags: boris karloff, brian de palma, Bruce Campbell, Charlton Heston, David Emge, Don Coscarelli, Elvis Presley, frankenstein, Gaylen Ross, George A. Romero, Horror, jamie lee curtis, JFK, Joe R. Lansdale, Ken Foree, Michael Myers, Ossie Davis, richard matheson, Scott H. Reiniger, Sissy Spacek, Stephen King, The Big Question, vampires, William Katt, Zombies

No Comments