If one takes NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD as the birth of the zombie outbreak – its true message, the politics of racism – there’s no stronger message than ending your film on a black man being killed by a “lynch mob” and DAWN OF THE DEAD as the life of the zombie outbreak – the message about the rabid, fetishistic consumption of consumerism – a message that still bleeds through into 2018, then DAY OF THE DEAD is about living in the afterlife of the zombie outbreak. The world has died, its pulse replaced with the cold flesh of cannibals roaming its overgrown terrain. The people who would’ve remained sane at the start of the end of the world are gone, or driven irrevocably insane by all the death and tragedy they’ve seen. The world is in tatters, and like all messes, no one knows where to start cleaning, or what pieces need to be put back together to start again. There are those bright spots of humanity left who work to fix the problem, or who strive towards a solution – essentially raging against the dying of the light despite it being at its dimmest. Then, there are the others who revel in the chaos. There are the merciless ones who thirst for violence and relish the power they wield, no matter how small in the world’s leftovers. For DAY OF THE DEAD, it’s the military versus the civilians, the immovable objects versus the irresistible forces. This is the power struggle at the core of DAY OF THE DEAD.

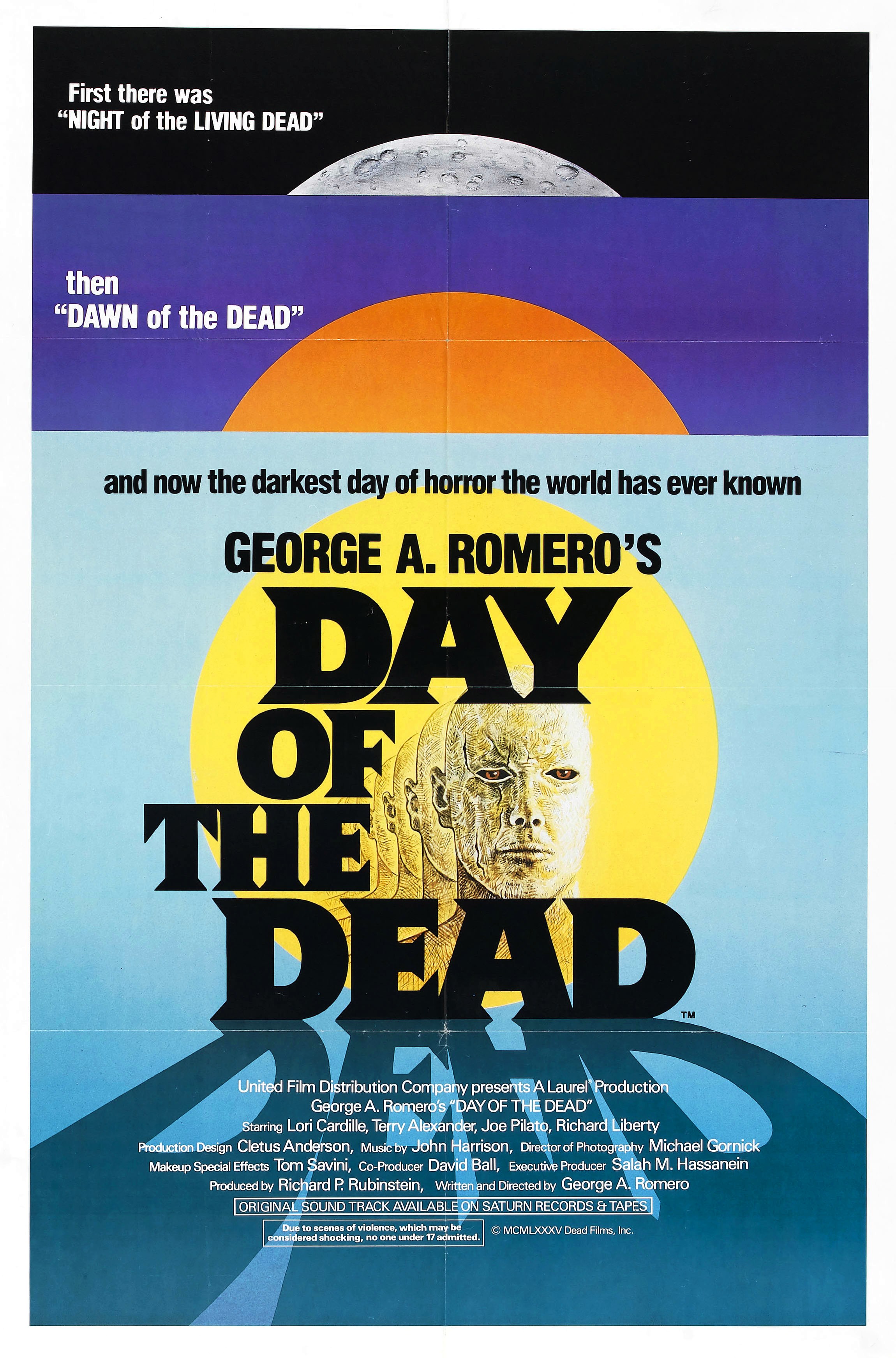

DAY OF THE DEAD was compromised from the start – Romero’s massive script was whittled down from over two hundred pages to the skin-tight script he filmed. He cleaved out parts of the potentially big-budgeted film (nearly a hundred plus pages), going from a budget of seven million dollars with an R-rating to three point five million for an unrated release, later massaging some of the script elements into DEAD RECKONING, or as it’s now known, LAND OF THE DEAD. This stripped-down film works in its favor. DAY OF THE DEAD is Romero’s coldest film – one that centers upon a small group of survivors living in a missile silo adjacent bunker, struggling to survive the decaying dead outside and to avoid the violence of the vicious military maniacs on the inside. This in turn makes it a claustrophobic experience as well, with tight corridors and dark caves – where you wind up not knowing what’s worse in the end – dismemberment or suffocation or execution at the hands of a gun-toting captain.

Because of this, there’s roiling anger from both military and civilians, and to Romero’s credit, he doesn’t point fingers or attempt to suss out right from wrong. Even the good guys can be subject to cowardice or quick to anger. This lends nuance to the film. A major part of Roger Ebert’s complaints about the film were that the characters were unlikable maniacs: “unpleasant, violent and insane”, he tells us. But that’s the point. When the world has ended, it’s not all sunshine and lollipops. It’s about hard feelings and hard decisions. It’s brutal and tough. When John, the helicopter pilot, sums up his place in the bunker food chain that as pilot, he’s indispensable – he’s not saying it to be mean to our lead, Sarah, he’s telling her that it’s nothing personal, but that he knows his worth in the new world. Captain Rhodes might be the most despicable ‘eighties villain committed to celluloid, doling out racist remarks to John, or making leering passes at Sarah – but perhaps the cruelest act is executing Fisher, the innocent scientist who had the misfortune of being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

This isn’t to say that Romero isn’t able to wrangle macabre humor out of the proceedings. Jarlath Conroy’s McDermott has some poison-laden snark he deploys regularly, and though Gary Klar and Ralph Marrero’s Steel and Rickles come off as cackling, hyena-lite assholes, they deploy some twisted gallows humor. DAY feels similar to the EC Comics-esque CREEPSHOW that he made a few years earlier, complete with red and blue gelled scenes grotesque murder tapestries. Tom Savini’s special-effects work here are a career-best, pivoting away from the pastel gore of DAWN, to the profondo rosso blood that would permeate the splatter films he would captain all throughout the ‘eighties. His grand effect, the zombie leaning over and his guts tumbling out, was a major highlight, but the “gore-gy” he displays in the finale is a full-on vomitorium of the highest order, particularly the vocal cords stretching with the decapitating of the head. John Harrison works overtime to top his best musical composition work with CREEPSHOW on this score. The bassline that fills the opening scene is so thick, it could cut your throat, and the jangly, action-movie score makes you feel like you’re watching a well-written, but fucked up episode of The A-Team. His light Caribbean-flavored score accentuates the sweaty, Florida heat of DAY OF THE DEAD. It’s hard as hell to top Goblin in the horror score pantheon, but Harrison manages easily here.

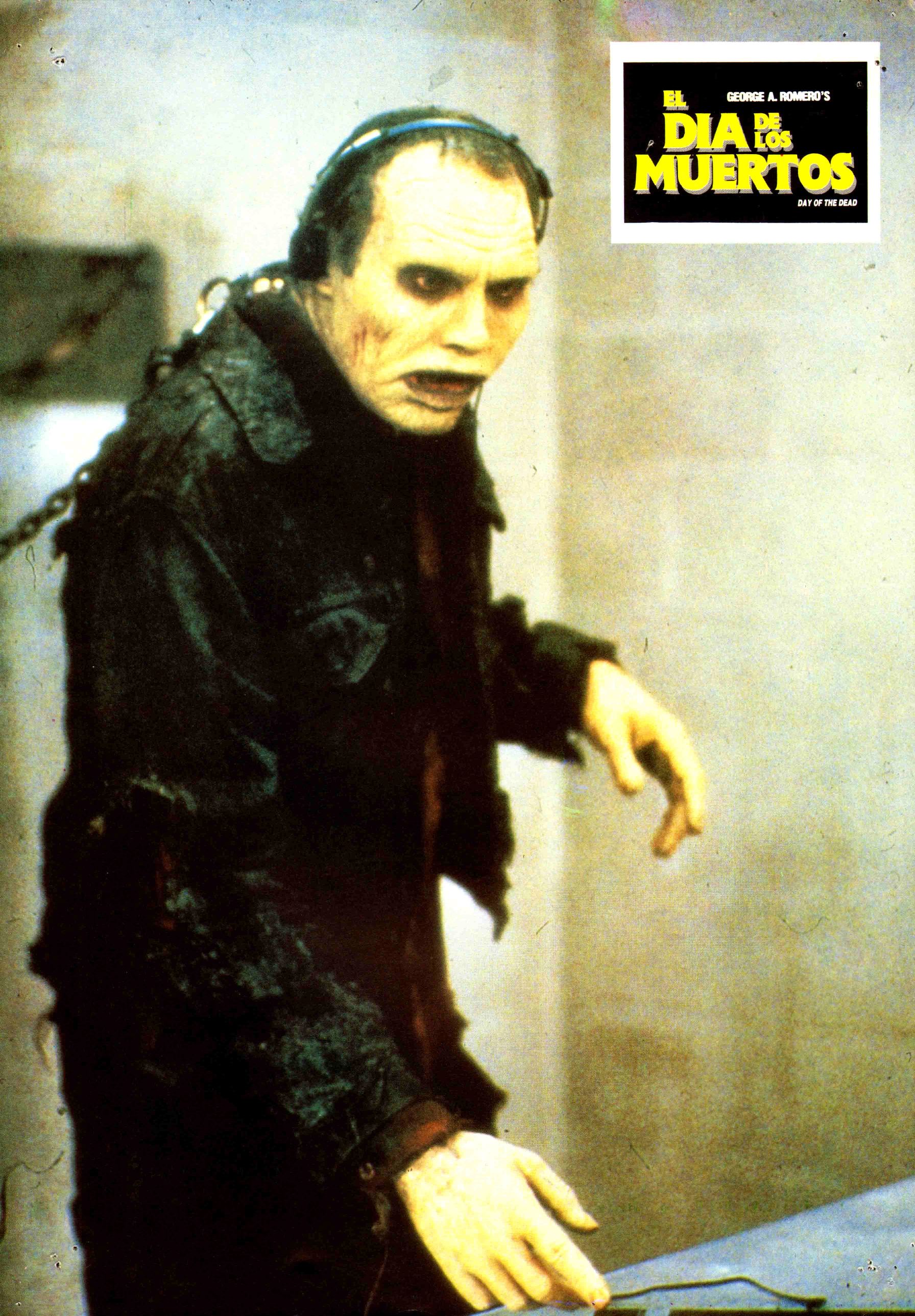

In reality, the only real humanity comes from Bub, the ex-military zombie that the bloody butcher Doctor Logan, née Frankenstein, has been training to regain his humanity. By virtue of strong writing and directing, and a hell of a performance by Sherman Howard (“IT’S A JUNIOR MINT!”), we’re given the first glimpse into Romero’s true franchise message – humans are assholes and the dead are the real heroes, and Bub is essentially Patient Zero. When Logan is executed at the film’s climax, Bub’s reaction is not to consume the dead flesh, but to weep for the departed doc – his second loss, the first being his life. This rehabilitation tack that Romero takes is a nice touch, because the idea of a cure isn’t something that would fix the overwhelming zombie problem, as Logan mentions, there’s too goddamn many of them. You can’t cure an addiction to heroin, so the only thing you can do is to reset and redirect the addiction.

It’s equally important that DAY OF THE DEAD is the film where religion takes a prominent place in its characters’ lives. Though briefly touched upon in DAWN OF THE DEAD with the old priest in the tenement having given the dead their last rites, “When the dead walk, senores, we must stop the killing … or lose the war,” or the scene with Frannie and the nun (the only zombie Romero ever refused to kill), it’s given a full-throated front seat here in DAY.

“You want to put some kind of explanation down here before you leave? Here’s one as good as any you’re likely to find. We’re bein’ punished by the Creator. He visited a curse on us. So that man could look at… what Hell was like. Maybe He didn’t want to see us blow ourselves up, put a big hole in the sky. Maybe He just wanted to show us He’s still the Boss Man. Maybe He figure, we was gettin’ too big for our britches, tryin’ to figure His shit out.”

One could fill an entire article digesting John’s sermon about God occurring deep in Act Two, that the heretofore-unknown zombie apocalypse was not one created by man, missile (or Russian satellite) or misfortune, but by a higher power, declaring spiritual warfare on the entirety of humanity. When we say that God works in mysterious ways, perhaps this is what we mean. This is a message, crying out that we fucked it all up through our anger, malice and misguided prayers; our theological attempts to discover the true meaning of the Why of it all only caused disproportionate retribution. There’s a kind of cruelty to it, that when we die, we’re not released into whatever peace we believe in – we’re doomed to wander the Earth starving for the flesh of humans, relegated to rot into a putrefying pudding and not eternal sleep. Or you could spend your last days on Earth thinking that you were being punished by a force you never met, for actions you never committed. But the dichotomy to this is that one could find the religious aspect of it as somewhat of a cold comfort. If the zombie apocalypse is unexplainable by any of the foundations of science or man, perhaps we would look to the higher powers that be as some sort of reason for what’s happening to us all. And if it is religion then at least it’s something. At least it means that despite all the horror that swirls around you in your everyday life, perhaps there is an afterlife.

DAY OF THE DEAD was released in theatres on July 19th, 1985 – exactly thirty-three years ago today. It’s a somber anniversary for zombie fans everywhere, as we just passed the one-year anniversary of George A. Romero’s death on July 16th, 2017. The film was sadly critically misaligned, a box office failure, and at the time, it seemed like the end for the DEAD films forever. Fortunately, over the next three decades, the response of critics and fans have been kinder to it, leading to some folks, including myself, to decree it to be Romero’s best-made film (with MARTIN a close second), though I personally consider DAWN OF THE DEAD to be the best film ever made. The tragedy of filmmakers passing away, especially with those who have maligned entries in their filmographies, is that they pass on long before their mistreated works are re-evaluated with fresh eyes and a fresher mind and given appreciation. In Romero’s case, before his passing, he knew that horror fans truly loved DAY OF THE DEAD and that it finally had gotten the grand treatment it deserved.

That feels like a nice note to go out on. Stay scary, George.

Tags: Alligators, Anthony Dileo Jr., Florida, Gary Howard Klar, George A. Romero, Gregory Nicotero, Helicopters, Jarlath Conroy, Joe Pilato, John Amplas, John Harrison, Lori Cardille, Michael Gornick, Modern Man, Pasquale Buba, Pennsylvania, Phillip G. Kellams, Ralph Marrero, Richard Liberty, Richard P. Rubinstein, Sherman Howard, Sputzy Sparacino, Taso Stavrakis, Terry Alexander, tom savini, Zombies

Great write-up. My favourite zombie film of all time and in my top 5 films of all time.