To celebrate the November 16, 1984 release of A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET, Nathan Smith and Brett Gallman are spending every day this week reflecting on Wes Craven’s seminal film and its legacy. In case you missed it, here’s Part One and Part Two.

Part Three

Grab Your Crucifix

“One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light,

but by making the darkness conscious.”

— Carl Gustav Jung

Nathan: Brett, you asked if I was a bigger fan of 1984’s A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET’s fantasy sequences being on the more “realistic” dream-like wavelength of PHANTASM or what the ELM STREET sequels did with the more elaborate nightmare scenarios. It’s the former, actually. Something the 1984 film does that the others don’t is relegate the actual visuals of the nightmares to our heroines alone. Later entries would give every character, victim or otherwise, wildly designed nightmares, but Craven wisely leaves viewing of the horrific bad dreams to Tina and Nancy (interestingly, we don’t see Nancy go into his world until after Tina’s death) other than the spooky iconic shot of Freddy pushing through the wall. This allows for a laser focus on crafting Krueger’s landscape without relying on their personalities for Freddy to dole out his brand of punishment, which additionally is something the sequels are too reliant on (to a fault). It’s almost like the nightmares here are crafted using their memories against them. Nancy has probably walked to the police station a hundred times, but now, her brain is firing the dream synapses in random order, meaning that she has to go through the alley behind Tina’s house (it’s not too surprising she would have her friend on her subconscious mind) to get to her destination of the local jail house. Back in 1984, they didn’t need a gigantic budget to realize the landscape of what Freddy was creating, they used all those tricks in camera like Freddy’s elongated arms, which is such an absurd, terrifying image. The abstract, disjointed nature of Craven’s vision of Freddy’s nightmare-world is definitely something that electrifies my viewings now as an adult.

When you’re younger, you don’t really wrestle with the nature of dreams, they’re just something that happens. But aging leads to recognition that dreams and nightmares are an extension of our waking lives and, again, it’s masterfully exploited here. There are two executions of nightmares in ELM STREET that stick out to me. The climactic sequence where Freddy is chasing Nancy who runs up her stairs, only to have her feet get gummed up by Freddy physical altering the stairs into some goop. It’s relatable as we tend experience our actions differently in dreams and nightmares, slowing them down or inhibiting their effectiveness in ways hard to explain; try throwing a punch in a dream and you’ll feel like you’re underwater.

In the most high and palmy state of Rome,

A little ere the mightiest Julius fell.

The grave stood tenantless and the sheeted dead

Did squeak and gibber in the Roman streets.

As stars with trains of fire and dews of blood,

Disasters in the sun; and the moist star,

Upon whose influence Neptune’s empire stands,

…

Oh, God, I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself a

king of infinite space were it not that I have bad dreams.

The other scene that stands out to me is when Nancy is asleep in school and the student is up in front of the class reading from Hamlet (combining two different speeches by two different characters from two different scenes). His voice grows increasingly lower, the intonations increasingly spooky as reality subsides, the ground gives way, and the nightmare begins. It’s chilling and happens in only a few minutes but is an incredibly effective way to show that something is wrong. In this first film, Freddy’s primary targets seem to be either “lunatic” juvenile delinquents like Rod or children from broken homes like Tina or Nancy (would you believe that I never picked up on the fact that the Thompson parents were divorced or separated?) – the first interaction that Nancy’s parents have post-Tina’s murder is for Donald (Saxon) to gripe at Marge (Ronee Blakley) for letting Nancy be there in the first place, rather than fret over their daughter’s well-being. The one place where these teens find should find sanctuary from their mangled reality, their dreams, is no longer an escape but instead a battleground with very real stakes.

We’re both parents and something that struck me deeply upon my revisit was how much I related to the parents this go-round, specifically Marge—I mean, definitely not in the “slapping my child” way, though. As our children grow older and become more curious about the world in which they’re growing up, we feel a pull to lie to them about the more vicious parts of life. We think it’s protecting them but, in reality, it’s harming them. They need to know to an extent that the world has teeth and it’s all too happy to bite. Blakley’s performance, infused with the drunken, demented melancholia of a Tennessee Williams heroine, feels tangible as she drowns her dark secrets in an increasing number of bottles of alcohol. Unlike Donald and the parents in the sequels, she is actively invested in protecting and helping her daughter. She takes Nancy to the sleep study and is the one that is behind putting the bars on the windows. Only when she finally reveals the truth behind Krueger’s origins—the parents’ actions, their secret transgression—she’s finally free, but at what cost? She’s murdered by Freddy, furthering her daughter’s trauma. On a side note, I think one of the big mistakes of the movie is omitting that Marge was the one who literally killed Krueger (something that I’ve only heard in rumor circles), shooting him in the head when the fire didn’t completely destroy him. This would’ve put a nice bow on Freddy killing her at the film’s end.

“A bunch of us parents got together and tracked him down. We found him in old abandoned boiler room, where he used to take his kids.”

Glen’s parents cast their stones from across the street, thinking that Nancy is the weirdo daughter of the town drunk. Being a bunch of gossips worrying more about what’s happening in others’ living rooms than what’s going on in their own domiciles grounds the film in a familiar setting. And the result of peering outside instead of looking within? The local boogeyman purées their son. Donald’s stubbornness and disbelief in what his daughter is telling him is what gets Rod ultimately killed. That helps make the turn at the end of the film where the Lieutenant finally sees Freddy for real satisfying and allows for a sense of relief that her father finally believes her—though DREAM WARRIORS would later turn this relief against fans, fracturing the Thompsons’ relationship even further. Putting yourself in his shoes for a moment, would you believe your child if they told you that a man you had a hand in murdering is killing your school chums? Probably not.

Brett, do you feel the relatability toward the Thompsons and the lengths they go in protecting their daughter from the boogeyman, the lying and the murder as something reasonable or as something irresponsible? Their rationale being that if they did not murder Krueger, he would’ve invariably picked right back up where he left off. Secondly, do you see Marge’s death at the end of the film as a twisted karmic touch for her actions against Freddy?

Brett: You know, one thing that’s really remained consistent throughout my life is just how much I see Marge as a villain in the original movie, but you make a compelling case that maybe she isn’t. You’re right that she actually does take an active role in protecting in Nancy, even if she dismisses all of the stuff her daughter says about Freddy. Putting myself into that position does change things: it probably would sound like nonsense, and I think maybe Marge’s fate—getting blackout drunk and literally barring her child from leaving the house—might just be a desperation heave once she becomes consumed by both her own guilt and her acceptance that something strange is definitely going on. As much as I would find Nancy’s story hard to believe, I would also feel totally helpless in the face of this situation, especially since I would have played an unwitting part in it. Later sequels rarely treated parental figures with this sort of nuance, which I think is another testament to Craven’s understanding of human nature.

While the series would always thrive on an “us against them” dynamic with the teens and their parents, the original is the best at capturing just how inexplicable this nightmare would be for the latter. If I’m not mistaken, Craven’s original script actually did feature Marge shooting Freddy, which would give the ending a new level of meaning had it remained intact. As is, I see Freddy killing her as more a matter of convenience? Honestly, the ending of the original film remains kind of wonky and hazy even after seeing it a million times: I’ve always assumed Freddy was somehow using her to escape back into the dream world since she was asleep, but who knows? I don’t think this is a detriment to the film at all, by the way—I love how loopy and weird it is because that’s nightmare logic.

Nathan: I’ve never thought of it that way – that Freddy is using Marge to escape back into his comfortable Little Nemo-esque slumberland. When I was a kid, and this is the God’s honest truth, I thought that Freddy was “assaulting” Marge because to me … that’s what that looked like. As an older person though, I see that they’re just struggling and he’s burning her alive. This may not have been Craven’s intention, but I see the scene now as Freddy realizing his failure in getting revenge on Marge–his killer according to Craven’s script—by murdering Nancy, so he just cuts straight through the muck and slays Marge. When a murder door closes, a manslaughter window opens, if you will. The way her death scene is staged is so spooky with the fog and the skeleton slowly lowering into the bed, like Freddy taunting Nancy and Donald that he has both Marge’s soul and mortal remains. And dammit, I love Freddy’s reemergence into reality, pushing up through the sheet on the bed (the blood pooling on the sheet is *chef’s kiss*), the groans of the bed shifting to adjust for his mass and then finally he slices through the cloth, hatching like an egg. It’s a scene so nice, Craven used it twice, as it later appears in NEW NIGHTMARE.

“Hey Nancy! No running in the hallway!”

I want to use this moment now to talk about Krueger. I’ve always liked that Craven explored his villains through their inhumanity, flavoring their personalities with just enough spice to make them fictional horror movie characters but grounded enough in reality to make you feel like they live on your street. It’s something he did well enough with the aptly named Krug in THE LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT—a character that was only slightly over the top in some scenes, but a rabid dog in others. It’s a fascination with men and the evil they do. Krueger is a demon who thrives in dreamland, using paranormal powers (which thank God is left vague, Freddy is already a scary enough creation that we don’t need further exposition to bog the plot’s propulsion), but in reality he was a custodian at your children’s local school. He’s someone that interacts with your brood daily, whether you know it or not. This makes it scarier than an unnamable, faceless evil like Michael Myers or a hulking, unstoppable being like Jason Voorhees; Freddy Krueger is an evil that you take home with you, an evil that no one, not even the law, can stop.

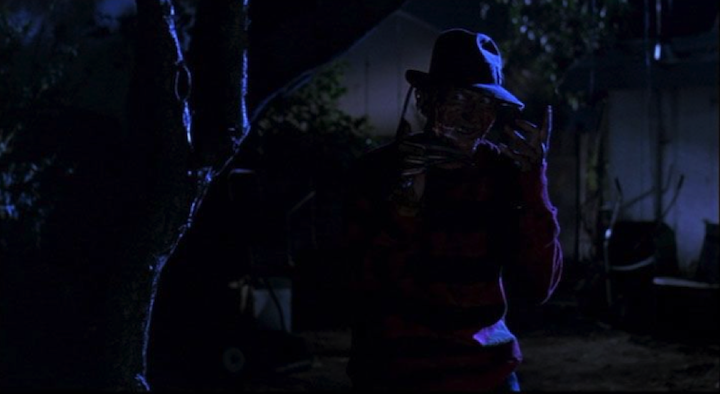

My friend Chris and I always joke about a clip from Bravo’s 100 Scariest Movie Moments, in which Clive Barker laments that Freddy has become “a joker.” Here Craven keeps Krueger’s appearances to a minimum, shrouded in shadows for nearly the entirety of the runtime, his words minimal—often threatening Nancy with phrases like “I’ll kill you slow!” Nearly everything he says is charged with a violent, psychosexual slant (“I’m going to split you in two”), which is the best and most frightening approach. When the sequels decided that having Freddy become a Catskills comedian be the series’ modus operandi, it somewhat neuters the character’s menace. Other than Craven’s script and direction, the real reason this character works so unnervingly well is Robert Englund’s landmark performance. The way he inhabits Krueger is a testament to his prowess as a character actor, the choices he made in giving Freddy a leaning gaunt, as he wields the claw like an old west gunslinger. The choice to play Freddy as a perverted creature was all Englund’s choice, as he told Gorezone: “When we read about abusers and molesters in the newspaper, they’re not big, hulking men, but weasels. I thought he should go in and play it like that. And it worked!” As great and timeless as Englund is, I’d be fascinated to see how the two other choices for Freddy would’ve played–Kane Hodder and David Warner. Hodder often plays his characters like they are an outlet for his internal rage while Warner has a soft, approachable, very professorial nature about him which goes against how we know Freddy today, which is a sleazy, sneaky slime ball. Tomorrow, let’s dig into your thoughts on Englund’s performance as Freddy. Also, how do you think these alternate castings might have turned out?

Tune in tomorrow for Part Four with Brett’s thoughts on Robert Englund’s performance as Freddy Krueger and both writers discuss the ending of A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET.

Tags: A Nightmare on Elm Street, Amanda Wyss, Charles Bernstein, Freddy Krueger, Freddy's Nightmares, Heather Langenkamp, John Saxon, Johnny Depp, Jsu Garcia, new line cinema, Robert Englund, Robert Shaye, Ronee Blakley, Wes Craven

No Comments