Scream Factory’s march through the Universal vaults arrives at the 1950s and beyond with its sixth volume, with this edition including some somewhat forgotten lore. Following a decade that saw Universal lean heavily on largely formulaic franchise filmmaking, the ’50s were a veritable wild west for the studio, which found itself trying to keep up with a bold new genre landscape that was looking to different sources of horror. This volume provides a fine snapshot of a studio and a genre at a crossroads with an eclectic mix of gothic staples, cult horror, and a paranoiac thriller hailing from across the pond, where an upstart British studio would soon prove instrumental in helping Universal cross the threshold into the next era.

THE BLACK CASTLE (1952)

One of Universal’s earliest 1950s horror ventures looked to the past, when the genre thrived on tales of madmen lording over bleak manors with sinister dungeons. THE BLACK CASTLE is not strictly an update on such films, but it feels of a piece with them even as Nathan Juran infuses it with a bit of adventurous pulp. The opening sequence is unmistakably the stuff of gothic horror, though: the camera prowls about an eerie countryside scene, leaves swirling in the howling wind as we move into a decrepit crypt, where a pair of men set about sealing a couple of corpses in their tombs. One of the dead is an unnervingly wide-eyed man who’s soon revealed to not be dead at all; rather, he’s in a paralyzed state, his mind frantically racing as these two men unwittingly begin to bury him alive.

A flashback puts us on the path to unraveling this bizarre scene. We learn that the paralyzed man is Sir Ronald Burton (Richard Green), an English gentleman who assumes a secret identity when travelling to the castle of the nefarious Count Carl von Bruno (Stephen McNally). Under the guise of participating in a hunt, Burton has actually arrived to discover the fate of two missing comrades he suspects ran afoul of the count. Burton and his friends have a long history with the madman, having skirmished with him during a war in Africa that left the count deposed, humiliated, and missing an eye. Before retreating to his German homeland, the Count vowed revenge, and Burton’s rescue mission soon becomes a quest for vengeance of his own.

Despite its gothic trimmings and evocatively portentous title, THE BLACK CASTLE soon yields to melodrama as Burton falls for von Bruno’s besieged wife Elga (Rita Corday). The Count’s second wife following his first betrothed’s untimely (read: “untimely”) demise, Elga resents living under the man’s ruthless, iron fist. Much of the early-going hinges on the uneasy, almost playful interplay between von Bruno and Burton; the Count is shifty enough that you’re never quite sure if he’s onto his old rival. There are times — such as when he seemingly orchestrates an ambush involving a leopard on the hunting grounds — when it feels like he’s simply playing along with Burton’s disguise and delighting in tormenting him. At others, he seems completely oblivious, leading you to believe that von Bruno is simply an asshole. The latter is most certainly true, as McNally is a wonderfully unhinged madman, sneering with a haughty contempt at everyone: his guests, his wife, his various lackeys. He’s certainly the film’s most dominant presence, which is no small feat considering both Boris Karloff and Lon Chaney (making his last appearance in a Universal horror production) provide supporting roles. In fact, one of the film’s weaknesses is that our hero Burton is fairly well overshadowed by those around him, reduced to an unremarkable, bland leading man who starts to feel more like conduit for the wild plot than an actual character.

The cat-and-mouse game between von Bruno and Burton eventually escalates into a full-blown web of intrigue involving shifting loyalties, poison, and a byzantine series of twists and turns to bring the story back around to the frame narrative, where Burton still rests comatose in a coffin. All the while, that gothic trimming shades the story, particularly with the combined presence of Karloff and Chaney, now serving as the genre’s old guard. Karloff is Meissen, von Bruno’s doctor, whose methods may or may not be completely mad, while Chaney plays the smaller role of a mute brute. There’s almost a meta touch to these two acting as vanguards of yet another spooky abode crawling with torture implements and a trapdoor that leads to a pit of alligators. Once the headlining acts, they’re now trying to get the next generation over with audiences, a path the two legends would largely stay on for the remainder of their careers.

Eventually, those horrific seeds — the dank crypts, gloomy dungeons, the ravenous alligators — flourish during an exciting climax. Burton and the Count’s final showdown is a bit lackluster, but otherwise THE BLACK CASTLE deftly blends horror, suspense, and melodrama into a typically sturdy Universal production. The studio’s genre wing might as well have been a sausage factory at this point but these productions remained impressive nonetheless, sporting elaborately designed sets and sharp photography. This is no exception, and, in retrospect, stands as a historical curiosity dwelling at the genre’s crossroads. By 1952, horror hadn’t quite taken to the skies or thoroughly explored the nuclear fallout of the atomic age, leaving this movie feeling a little anachronistic in hindsight. I’m not sure if contemporary audiences would have considered it old hat or a throwback to a bygone era; either way, it doesn’t at all portend the extraterrestrial and nuclear horrors yet to come during this bold new decade that would soon leave the likes of THE BLACK CASTLE behind.

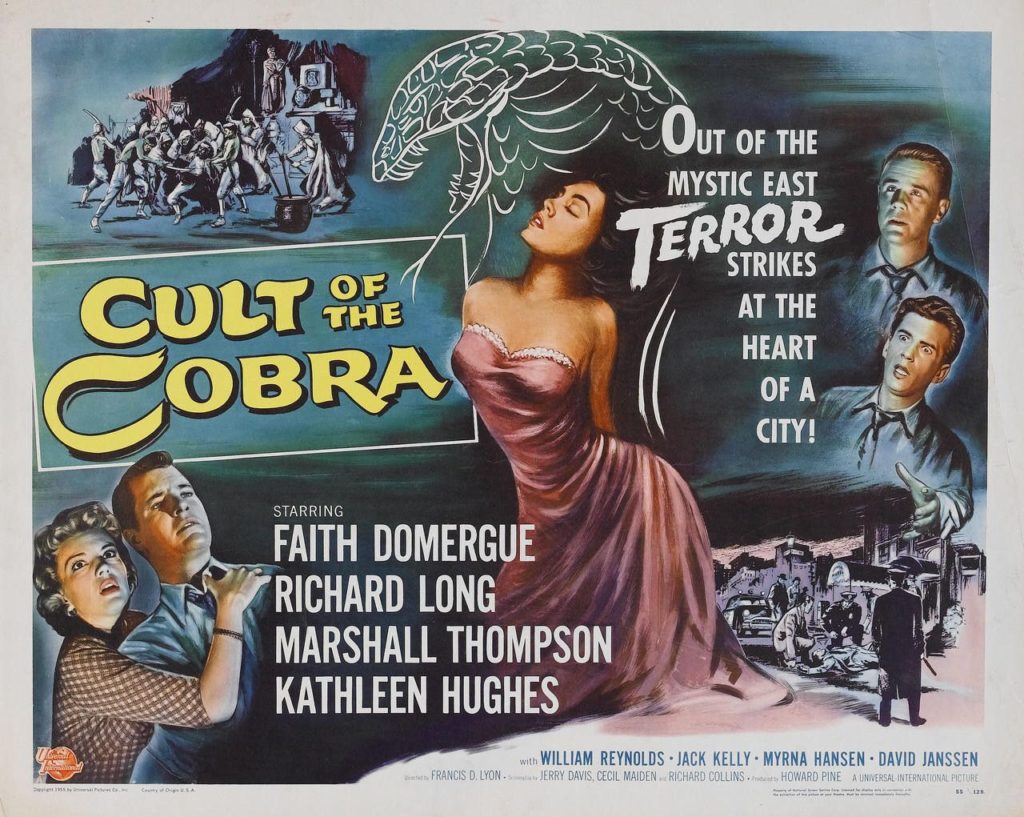

CULT OF THE COBRA (1955)

Then again, CULT OF THE COBRA is a reminder that no decade ever completely moves on from previous eras. Like THE BLACK CASTLE, it feels a bit anachronistic in more ways than one: not only is it another CAT PEOPLE riff produced thirteen years after Val Lewton’s classic, but it came just a decade after Universal already released their first riff with the Ape Woman trilogy. I have to think this one would have most definitely felt like old hat, or maybe even a nostalgic piece appealing to viewers who would have been missing this genre staple, kind of like how so many of us gravitate towards slasher movie homages now. At any rate, it’s an exceptional take that speaks to Universal’s ability to make even the most familiar material sing.

It’s even a period piece in its own right, albeit one only set ten years in the past, during the waning days of World War II, where six American soldiers find themselves winding down their service time in Asia. During their last night on the town before their return home, they attend a religious ceremony involving a local cobra cult that insists on an ancient belief that humans can transform into snakes. Despite stern warnings to remain undetected, they can’t help themselves by snapping some photos and trying to swipe one of the artifacts. Enraged, the cult leader curses the group, pronouncing death upon all of them and inciting his cult to slay the men’s local emissary as the temple burns to the ground.

One of the group doesn’t even make the trip home after succumbing to a snake bite later that night, an ominous portent of the horrors that await in New York City. Just days after settling in, Tom Markel (Marshall Thompson) discovers he has a new, exotic neighbor named Lisa (Faith Domergue), whose mysterious but charming nature fascinates him. Her resistance to his advances only emboldens him until they’re finally a couple, though their courtship coincides with tragedy when the surviving members of the platoon meet with their grisly demise in bizarre “accidents.”

What follows is the familiar tale of exotic, foreign terrors being visited upon the homefront, the core anxiety of so much Victorian and early 20th century horror. The notion of an ancient, old world “evil” that’s been repressed by modern society reemerging to wreak havoc is the vague throughline of this time period, and I wonder if it wouldn’t have resonated even more in the ’50s, when technological advances were sweeping through the world. CULT OF THE COBRA hinges on the idea of the Other, its dynamic defined by the tight-knit American platoon essentially waging war with a culture it perceives only as backwards and primitive. What’s remarkable here is just how boorish and shitty these guys really are: they are completely at fault for intruding upon a sacred ceremony and defiling it with their inconsiderate curiosity. Frankly, they deserve some retribution, and a more interesting movie might tackle it from that angle.

Of course, in 1955, you weren’t about to get a B-movie programmer that dared to question America’s complicity in reckless imperialism, so CULT OF THE COBRA ultimately seeks to reinforce America’s (and particularly the American male’s) status as an essentially agent of good. Much like its double-feature companion REVENGE OF THE CREATURE, it’s the story of American interlopers dabbling with ancient forces but remaining the victims when the situation spirals out of control. There’s very little conscience to these films in this respect: despite instigating the violence, the Americans are positioned as heroes and victims.

In fact, it’s ultimately Lisa who must grow a conscience and reckon with the ancient forces that have dispatched her to take retribution. For much of the film, it looks like she’ll be an unrepentant agent of vengeance, slithering through these men’s lives undetected as one of them swoons for her, completely oblivious of the horrors she’s unleashing. But in true CAT PEOPLE fashion (and there’s even a jump scare involving a bus to confirm the homage), Lisa eventually begins to struggle with the ancient horrors lurking within her, particularly when she begins to fall for Tom. The final third of CULT OF THE COBRA is melodramatic once the truth comes into focus: Tom doesn’t want to believe Lisa is capable of such evil, while she wishes she could resist her primal urges. While it doesn’t quite rise to the psychological or dramatic heights of the more ambiguous CAT PEOPLE, it’s quite gripping, especially when the climax intermingles body and existential horror during Tom’s confrontation with Lisa. There’s something unnerving about the sight of a man grappling with a snake without realizing it’s actually the woman he loves as he attempts to shove it out of a window. Even though CULT OF THE COBRA is fairly light-on-its-feet pulp for much of its runtime, it ultimately lands a sublime, melancholy punch.

It’s a testament to the strong filmmaking on display that you’re not just left with déjà vu. The cast is tremendous, full of actors that would go on to have prolific television careers. Anchoring the picture, however, is Domergue, a late replacement for Mari Blanchard on the production. Already a screen staple by 1955, Domergue would soon become synonymous with genre films throughout the rest of the decade. Her turn in CULT OF THE COBRA feels almost haunted by a wayward sense of sadness: she’s utterly captivating yet somehow distant at all times in a quintessential exotic woman performance. When Lisa finally begins to show remorse, her struggle is convincing, but Domergue is also careful to maintain a sense of helplessness. Lisa’s story can’t end in anything but tragedy, and this shadows Domergue’s performance throughout.

At the helm for CULT OF THE COBRA is Francis D. Lyon, a reliable studio hand who did everything from horror to westerns to television. His direction largely leans on the solid production values inherent to most Universal productions. What sets CULT apart is how much bigger it feels compared to its ‘40s predecessors: while much of it is confined to an obvious backlot, an abundance of sets and on-location establishing shots opens the picture up, giving it a sense of grandeur. The camerawork is dynamic too, particularly when capturing the attack sequences from stylish POV shots to heighten the suspense. It’s likely a utilitarian tactic too, one that allows the film to stage carnage without resorting to unconvincing (or expensive) effects. But that’s one of the many things that’s always made these Universal productions so fascinating: they often blur the line between A-movies and B-movies, top bills and lower bills. They were made expressly to entertain on a budget, and the ’50s productions especially just move and pop in a way that distinguishes them from previous efforts. As such, CULT OF THE COBRA might forever be in the shadow of CAT PEOPLE but it makes a spirited attempt at slithering away from it all the same.

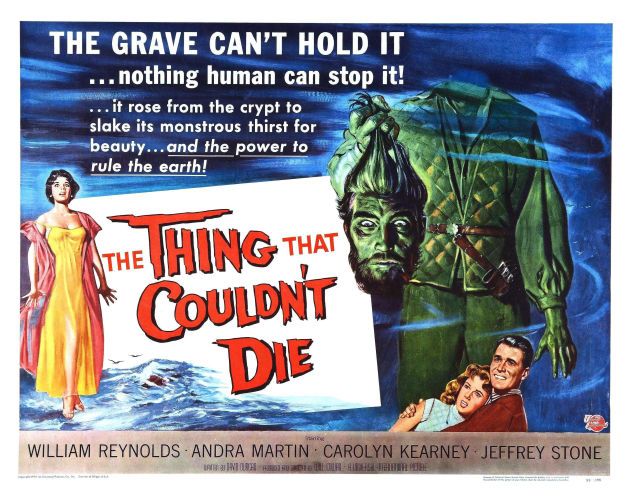

THE THING THAT COULDN’T DIE (1958)

If you need evidence of Universal’s eclectic ’50s output, look no further than THE THING THAT COULDN’T DIE, a bizarre occult horror nestled in with the era’s sci-fi-horror fare. It’s a movie whose reputation has preceded it for the past twenty years now, thanks to an appearance on MYSTERY SCIENCE THEATER 3000, an ignominious distinction or a badge of honor depending on your persuasion. I fall into the latter category because it must be said that the Satellite of Love crew did a lot to highlight the weird, forgotten corners of cinema and not just pan the absolute dreck. And this curious 1958 shocker is nothing if not quite strange, particularly for its time period, when a weird occult movie involving madness and curses stretching across generations would have stood in stark contrast.

Mysticism hangs thick in the air as we’re introduced to Jessica Burns (Carolyn Kearny), a supposed “water witch” capable of uncovering lost items on her aunt Flavia’s (Peggy Converse) ranch. She’ll only use her ability for altruistic purposes though, and refuses to help anyone satisfy their greed or lust for gold. During a dowsing expedition, however, she discovers a box buried nearby, one that bears a foreboding warning inscribed on the outside. Opening the box may cost your eternal soul, which isn’t too high of a price for Flavia, who’s counting money before they can even haul the chest inside.

Cooler heads prevail when gentleman caller Gordon Hawthorne (William Reynolds) suggests they should consult an archeologist first: after all, the trunk itself might be worth more than what’s inside. Before the archeologist can return, however, greedy ranch foreman (James Anderson) manipulates simpleminded but well-meaning handyman Mike (Charles Horvath) into prying open the chest, only to discover the still-living head of Gideon Drew, a 16th-century sorcerer who quickly sets to recovering his body so he can continue his reign of terror.

Say what you want about THE THING THAT COULDN’T DIE: yes, it’s a low-budget, small scale cheapie that unfolds in a single location, effectively diminishing its plot’s full potential. But what potential is on display here! This is a prime example of a movie that thrives on imagination and cool visuals even when it doesn’t quite have the means to quite pull it off. It’s a story soaked in a sordid mythology, as Jessica’s powers allow her to glimpse into the past to witness Gideon’s execution, where he’s sentenced to a living death, condemned to live without his body unless he can somehow reattach itself. It’s not the most foolproof plan, though, because here he is, 400 years later hypnotizing lackeys with a manic, wide-eyed gaze. Robin Hughes (who would go on to play Satan himself two years later on THE TWILIGHT ZONE) is an indelible presence despite little screen time. Even when he’s just a severed head, he commands the screen in such a way that the inherent hokiness subsides: Gideon Drew is a legitimately frightening presence who introduces chaos into this quaint, picturesque countryside.

It’s just too bad the film can’t properly accommodate him or his strange saga: his lackeys are ultimately responsible for all of the chaos (read: one grisly stabbing and some melodrama involving a couple on the ranch) until he’s resurrected, at which point he delivers a grandiose speech on the state of humanity before being promptly put back in his place within minutes. Anticlimactic isn’t quite the word for it: it’s almost like everyone involved couldn’t be bothered to come up with an entire third act of the film, so it quits just as it feels like it’s getting going. This likely owes to the obviously low-budget nature of a movie that was shot in two weeks on Universal’s backlot during the studio’s late-50s slump. The glory days of Universal horror were beginning to fade at this point, as it would ultimately take a distribution partnership with Hammer for the studio to regain its genre foothold.

Still, THE THING THAT COULDN’T DIE offers a fascinating glimpse into this late period, when Universal resorted to just about everything to keep its genre reputation afloat, be it an iconic monster in CREATURE FROM THE BLACK LAGOON, irradiated bugs in TARANTULA, the existential horror of man’s diminishing stature during the atomic age in THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING MAN, extraterrestrial terrors in THIS ISLAND EARTH, and even Old West vampires in CURSE OF THE UNDEAD. THE THING THAT COULDN’T DIE comfortably fits alongside because, well, everything had a place at the table during this time period, which makes it one of the most purely fun horror eras, even if it does feel like a stopgap between the towering pillars of the the golden era and the looming renaissance of the ‘60s and ‘70s.

I love the “anything goes” mentality driving something like THE THING THAT COULDN’T DIE, a movie that Frankensteins together its musical cues from older scores to surprising effect (the main title theme from THIS ISLAND EARTH is weirdly haunting played over shots of a desolate, foggy ranch here). A production like this moves even further down the spectrum in blurring the lines: this is unmistakably a B-movie that often feels more like unrepentant exploitation as it stages stuff that would have been ghastly during this time period, like Satanic invocations, an on-screen decapitation, and the sight of the virginal Jessica adopting a gothic wardrobe after giving herself over to dark forces. Screenwriter David Duncan stuffs a lot into a 69-minute runtime that would have been a big selling point: THE THING THAT COULDN’T DIE is the epitome of a drive-in experience that looks to thrill and shock audiences before shuffling them on to the next feature (which, in this case, was often THE HORROR OF DRACULA). Considering it as a warm-up in this respect does it some favors: it’s the noisy, messy opening act that shows glimpses of brilliance with some evocative, meticulously composed shots and its unhinged imagination, but it’ll never be mistaken for a headliner.

In retrospect, it’s also something of a rough draft that anticipates the occult horrors that would flourish in the coming decades, when Satan and his minions would rule supreme at the box office. Films like this and NIGHT OF THE DEMON provide early glimpses of the genre landscape yet to come, when occult mysticism and inexplicable evil would replace mad science in conjuring up horrors. Essentially, THE THING THAT COULDN’T DIE crawled so Paul Naschy could run with HORROR RISES FROM THE TOMB, an homage/remake that allowed this premise to reach its full potential. Some might point to this as the nadir of classic Universal horror, and even if that’s true, it must be said that even Universal’s worst proves to be a fascinating, downright fun historical curiosity when you consider its legacy.

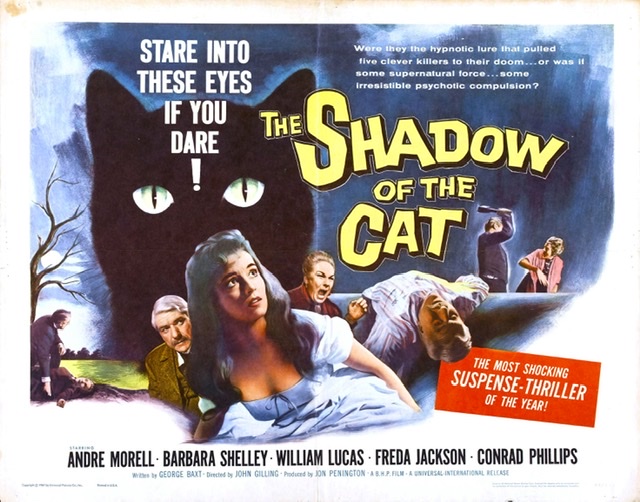

THE SHADOW OF THE CAT (1961)

The final entry in Volume 6 brings everything full circle with a dispatch from the early ‘60s, when what was old was new again thanks to the combined efforts of Hammer Films and American International Pictures. Gothic chillers and supernaturally-tinged murder mysteries were once again en vogue, and THE SHADOW OF THE CAT was one of several Hammer pictures Universal distributed during this time, effectively helping to repopularize the genre it established on this side of the Atlantic. THE SHADOW OF THE CAT specifically hails from Hammer’s thriller wing; while the British studio came into prominence for its lavish, colorful updates of old horror staples, it also churned out scores of elegantly crafted, black and white suspense movies, some of which (like SCREAM OF FEAR), rank among the studio’s best output.

This is an especially strange one that hinges on an outlandish premise: when elderly Ella Venable (Catherine Lacey) is murdered, we know exactly who commits the deed and why they do it. Her entire household — including her formerly loyal butler — is in on it so they can carve up her inheritance with a forged will. Unfortunately, someone else also knows they’ve done it: Ella’s cat, Tabitha, is witness to the deed, and everyone involved is convinced the feline will somehow reveal their secret. As more greedy family members descend on the house, they’re drawn further into a mad delusion that proves deadly as Tabitha seemingly leads these guilty, damned souls to their doom.

THE SHADOW OF THE CAT is a delightfully odd entry in the Hammer canon that lays all of its cards on the table and asks viewers to simply go with its wild premise. Hailing from a lot adjacent to the Old Dark House tradition, it sometimes has the look and feel of the burgeoning krimi movement as it tips its hat in the direction of Poe. Before her ill-fated encounter with her family, Ella recites “The Raven,” effectively setting the stage for the playfully askew mayhem that follows. Just as AIP often borrowed Poe titles to spin their own tales, THE SHADOW OF THE CAT takes the basic kernel of “The Black Cat” and runs with it as Ella’s family descends into madness, paranoia, and bickering, especially when they’re unable to locate the slain woman’s original will. All along, Tabitha slinks and purrs about the place, reminding them of their foul misdeeds before causing them to perish in horrific accidents (or are they “accidents?”) involving precarious staircases and quicksand. In some ways, it almost prefigures something like Bava’s BAY OF BLOOD: these are awful people squabbling over an undeserved inheritance who deserve the grisly comeuppance coming their way.

Of course, even Hammer wasn’t quite overboard with gore in the early ‘60s, so THE SHADOW OF THE CAT is restrained compared to the more outlandish splatter movies that would emerge in the coming decades. Director John Gilling, who helmed several standout Hammer productions (THE REPTILE, PLAGUE OF THE ZOMBIES), imprints the studio’s signature steadiness on the material: evocative, elegant camerawork captures a sumptuous production design, keeping the lurid story material couched in a classical, gothic framework. Even though the script doesn’t hoard many twists and turns, Gilling stages some nice jolts, many of them involving Tabitha herself. In so many films, cats are used for fake-out scares, but THE SHADOW OF THE CAT cleverly orchestrates some legitimately fun jumps with its vengeful feline. A demented guessing game emerges, coaxing the audience to wonder just how the next victim will meet their end, an approach that further anticipates the splatter movie theatrics of the coming decades.

It makes for an unexpectedly fun, playful experience: These characters are such unrepentant assholes that you delight in watching them squirm under the pressure of their paranoia. André Morell is particularly despicable as Walter, Ella’s husband and ringleader of the plot to kill her and claim her inheritance. He’s surrounded by several Hammer mainstays, most of whom appeared in several of the studio’s lesser heralded, non-franchise movies. Among them is Barbara Shelley, one of the great, unsung Hammer women, often overshadowed by the likes of Ingrid Pit and Hazel Court. Here, she plays Elizabeth, Ella’s favorite niece and the only one of her clan who isn’t in on the conspiracy, giving the audience something to gravitate towards besides rampant carnage. As much as you want to see Ella’s insidious family members bite it, you want to see Elizabeth uncover their fiendish plot and claim what’s rightfully hers.

THE SHADOW OF THE CAT is arguably the crown jewel of this sixth volume, if not one of the most noteworthy titles of Scream Factory’s entire Universal Horror series. It’s long been an essentially “lost” Hammer film, especially in the States, where it’s apparently never been released on home video from what I can gather. Bootleg copies sourced from British TV have circulated over the years, but they can surely be tossed out now thanks to this release. Quite frankly, it’s incredible that a Hammer production has been so obscure for so long, especially since THE SHADOW OF THE CAT is one of the studio’s more peculiar but rewarding efforts. Meticulously crafted gothic pulp, it’s also a minor historical curiosity if you’re charting the path to what would eventually become the giallo and slasher film — and it’s among the most offbeat, crooked signposts at that.

The discs:

Scream Factory has once again done a top notch job in bringing these titles to Blu-ray. Each film receives its own disc, giving the presentation plenty of space to breathe and eliminating the possibility of any compression artifacts. New 2K scans of fine-grain film elements were commissioned for each movie to boot, and they all look rather immaculate. The occasional shot goes soft here and there, but that often owes to the filmmaking techniques involved and the age of the source material. It’s hard to imagine these films ever looking and sounding better than they do here, especially since they’re all just now making their HD debut in the year 2020. Even in the unlikely scenario that these movies make it to 4K, you have to imagine it’s several years away.

As has been the case for most of these Universal Horror collections, the supplements are headlined by audio commentaries from an assortment of film historians. Tom Weaver provides a solo track on THE BLACK CASTLE and is joined by Steve Kronenberg, David Schecter, and Robert J. Kiss for CULT OF THE COBRA. C. Courtney Joyner teams with Weaver on THE THING THAT COULDN’T DIE, while Bruce G. Hallenbeck provides the track for THE SHADOW OF THE CAT. The latter film also boasts “In the Shadows of Shelly,” a newly produced interview with the actress that gives her a well-deserved spotlight. While SHADOW itself is only mentioned in passing, the actress recounts her career with Hammer and beyond, citing her early days in Italy before sharing memories about the studio’s towering icons, such as Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing. It’s such a treat to see anyone involved with these films share their first-hand accounts since so few of them are still with us.

THE BLACK CASTLE also boasts an unadvertised featurette titled “Universal Horror Strikes Back,” featuring the always infectious Kim Newman and Stephen Jones chatting for fifteen minutes about the studio’s ‘40s fare. They specifically address the APE WOMAN trilogy and discuss the appeal of this particular decade, specifically the sort of repertory nature of productions that often boasted the same recurring cast members. It seems like it would have been more appropriate for the previous volume since it featured these films, but I can’t help but wonder if the current pandemic made something go haywire there. It’s nice to have, regardless. Scream has also thrown in the typical assortment of trailers and still galleries for each film, too, plus a nice booklet featuring an assortment of poster art for each film.

Volume 6 is reportedly the last of this incredible run of films. If that’s the case, it’s only disappointing because you’d like to see more, even if few stones have been left unturned between these six volumes. Scream Factory has performed an incredible service for the genre’s history by preserving 24 films that were previously scattered to the home video winds by Universal itself, who spread these titles across various, random DVD collections over the years — if they were released at all (in addition to THE SHADOW OF THE CAT, 1945’s JUNGLE CAPTIVE also made its digital home video debut thanks to these collections). Because most of these films have always dwelled in the shadow of the towering Universal Monster stable, it was easy to imagine they’d never make it to Blu-Ray at all, much less as part of a lovingly crafted, multi-volume set like this.

Tags: B-Movies, Blu-ray, boris karloff, Faith Domergue, Horror, lon chaney, scream factory, Universal Horror

No Comments