To celebrate the November 16, 1984 release of A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET, Nathan Smith and Brett Gallman are spending every day this week reflecting on Wes Craven’s seminal film and its legacy. In case you missed the previous installments, here is Part One, Part Two, and Part Three.

Part Four

Gonna Stay Up Late

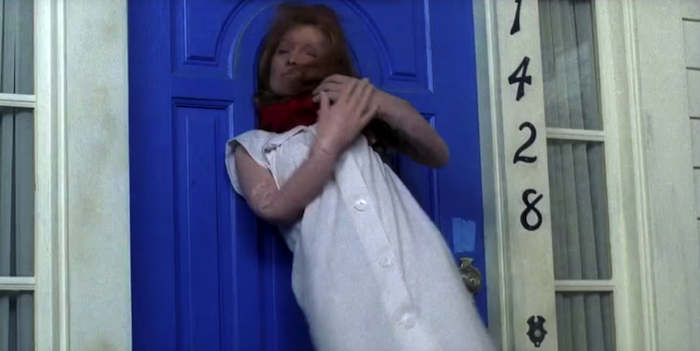

“I’m your boyfriend now, Nancy.”

Brett: Freddy is definitely one of those figures that has entered a rare plane as a character that’s inexorably tied to its performer. You simply can’t imagine anyone but Robert Englund playing Krueger, and WB’s ill-advised reboot attempt reinforced as much. Not that we needed it to, of course: I don’t think it’s blasphemous to say that Englund is Freddy at this point, and it’s going to take a helluva performance by someone to prove otherwise. Part of that is obviously just familiarity—at this point, he’s been associated with the role for over 30 years, and I suppose that creates a sort of unconscious bias. But I also think Englund genuinely shaped this character and etched Freddy into the public consciousness unlike his fellow horror icons. While I don’t think Craven could have ever envisioned (much less intended) for Freddy to take on the outsized personas he sports in the later sequels, that potential was always there, right from the beginning. Freddy isn’t just some lumbering brute that could be easily replaced; in many ways, he was probably always destined to be the franchise’s star, thanks to that crucial decision to allow Englund to really inhabit the role with a sardonic approach.

I’ve always laughed at the sentiment that Freddy “became” a joker in the later series myself, if only because the humor was always there. Granted, it was much more twisted, but his second encounter with Tina bears so many hallmarks of what makes Freddy great: sick one-liners (“this is God”), impish sight gags, and a fiendish mean streak underlying it all. Again, later sequels would definitely make a lot of this more pronounced and silly, but I’ve always felt this is what made Freddy, well, Freddy.

You make some good points about the physicality of Englund’s performance, which I’ve always thought has been unfairly overlooked throughout the years. There’s a slinkiness to Freddy that’s perfect for a creature that lurks in your subconscious, and it also emphasizes many of the points you made about Krueger silently operating right in the heart of suburbia. With the exception of his obviously ghoulish appearance, Freddy is practically an unassuming monster, perfectly capable of slithering like the phantom he is. I once read that Englund took inspiration from Klaus Kinski’s turn as Nosferatu, and I haven’t been unable to see that ever since, especially since NEW NIGHTMARE brought it full circle with the homage to Murnau’s original film.

Would anyone else have been able to do make Freddy such an indelible character? I’ll never say never, but I am pretty confident that any other take would have been markedly different. David Warner is the most fun possibility to speculate about since it came so close to happening, so much so that we even have pictures of the original make-up, but I still can’t wrap my head around that reality. Hell, I can’t even imagine Freddy rocking the paperboy cap Craven originally envisioned, even with the lone set picture that’s emerged of it over the years. It’d be fun to peer into an alternate universe and see if Warner could have been as enduring as Englund was, as it’s definitely one of horror’s greatest “what if?” scenarios. I don’t think it’s much of a stretch to attribute the success of the original film to Englund’s singular performance, and it’s obvious New Line quickly learned that too when they briefly tried to replace him with a stuntman in FREDDY’S REVENGE. Had Freddy just been a typical, generic slasher, the series may have gone on for a bit, just because I think the hook—a killer who stalks you in your dreams—is simply too intriguing (as can be seen by its many imitators); however, I doubt it would have lasted nearly as long as it has. Put it this way: I don’t know if we’d be sitting here writing this article in that alternate reality.

Let’s turn our thoughts towards the ending. As you said about the dreams throughout the movie, the ending kind of operates on that sinister wavelength where you can just tell something is subtly off, right down to the final scene. I love how Craven (and Bob Shaye, I guess, since he essentially hatched the ending) keeps you guessing about everything you’ve just witnessed. Nancy and the kids being driven away in a car commandeered by Freddy, whisked away to an uncertain fate as the Elm Street nursery rhyme girls jump rope is one of my favorite bits in A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET. It’s sort of a mirror image of the first time we see all four characters together: driving up to school, as that same nursery rhyme trails off. Are we meant to believe that the entire movie is one giant, looping nightmare? A premonition of events that have yet to really happen? Again, I know the real answer is that Craven and Shaye had disputes over how the movie should end, but I actually think this is a case where a producer-director clash resulted in the perfect ending.

I believe Craven disliked that it undercut his optimistic ending, but I’ve come to find that it comes to reinforce what’s so goddamn scary about this premise in the first place: just how can you reasonably defeat a boogeyman that lurks in your subconscious as a twisted byproduct of your parents’ sins? As I grow older, it’s a lot easier to read ELM STREET as a generational struggle about kids being forced to reckon with inherited trauma. There’s a universal appeal to that for sure, but I also think it’s perfectly pitched for these specific generations: the Thompsons and the other Elm Street parents hail from the generation that was forced to discover that the white-washed, picket-fence vision of suburban Americana was a myth once they discovered an unspeakable evil lurking in its midst. Their kids, on the other hand, will never know that kind of myth, which largely tracks with what these generations actually experienced. Freddy is kind of a boogeyman that reflects the turmoil and chaos these kids would have experienced growing up: the rising divorce rates, political turmoil, and just the growing sensation that there’s no real peace or comfort in the world.

I always found Craven to be very sympathetic towards younger generations in his films, and ELM STREET may have been the best example of that. I truly believe the film was him trying to wrestle with the experience of ’70s and ’80s kids growing up in a world that would have been much different from the one he saw growing up. Am I reading too much into this? Do you think the ending works or would you have preferred the original one? Is it too much of a stretch to see the entire movie as one giant nightmare premonition of events that are about to happen?

Nathan: Personally, I don’t see the ending as a premonition. I see Freddy maybe warping Nancy’s reality to toy with her even further, that her attempts to turn her back on evil and vanquish Krueger were all subliminal thoughts he put into her brain. The turn where this occurs would be somewhere after Rod is killed, right before she goes to the sleep clinic. This doesn’t make the events of the film a dream entirely, but all that Nancy sees or experiences is but a dream within a dream. It’s like a hall of mirrors—endless nightmares for Nancy—she thinks she’s woken up but it’s not the case. She is a pawn in Freddy’s dream scheme and this is how I choose to interpret him ripping Marge through the window above the door at the film’s last smash, they’re pieces he’s moving around the board. This is mostly amended by DREAM WARRIORS, but works greatly here.

“It’s too late, Krueger. I know the secret now. This is just a dream. You’re not alive. This whole thing is just a dream.”

The ending works just fine as it is, open-ended for a sequel but thankfully retains the ominous mood that Craven cultivated throughout—it’s a creepy stinger with the jump roping girls and the car with the Freddy sweater theme If it were to be a standalone film as he initially intended, then yeah, I would’ve preferred a more optimistic ending. I suppose the cynical answer is that the interpretation behind the ending is Bob Shaye and New Line Cinema saw the potential for this thing making money and therefore goading Craven into fusing their endings where the door is cracked open just a smidge, that Freddy isn’t quite dead, and that he can go on to torment a poor repressed teenager. It obviously played like gangbusters and became a lucrative entity for New Line, which we can discuss in a bit, but this is the rare instance where executive meddling actually played well for both parties.

I want to shift to discussing Charles Bernstein’s amazing score now. It’s inarguably one of horror cinema’s finest compositions, an instantly recognizable piece of music that as we both discussed would rank right up there with John Carpenter’s work on HALLOWEEN. The way he fills the music with the recurring piano leitmotif shaping it to fit whatever haunting imagery is on screen is utterly brilliant. The mood of the score reminds me in a lot of ways of a ghostly choir singing in the halls of an abandoned cathedral. “School Horror/Stay Awake” is the piece that congeals all the notes into a whole piece that serves as A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET‘s aural statement. Other pieces like “Run Nancy” or “Terror in the Tub” serve as electrically charged pieces that amp up the audience’s pulse and serve as alternate tracks for teenagers to groove on in some dance club from hell. And Bernstein does a great job at achieving a Carpenter-esque nirvana with “No Escape.” The scores for the other films in the franchise don’t stick to my ribs in the way that Bernstein’s does, save for Angelo Badlamenti’s frenzied take in DREAM WARRIORS or Brian May’s work on FREDDY’S DEAD: THE FINAL NIGHTMARE. Brett, what do you think about Bernstein’s score?

Brett: Bernstein’s main ELM STREET theme is neck-and-neck with Carpenter’s immortal HALLOWEEN work. I honestly think it’s those two compositions…and then everything else. I can’t really imagine pitting them together in any way, so I’ll just say that each is perfect for their respective films. Bernstein’s score has an ethereal, lingering quality that changes tenors and pitch, which captures the weird, flitting quality of nightmares. Where Carpenter’s HALLOWEEN theme mostly evokes nostalgia at first blush, the ELM STREET theme is still genuinely spooky. Those more frenzied bits of the score are terrific to be sure, but, to me, I’ve always loved the haunting bits that linger over the film’s quieter moments, like the opening bars of “No Escape.” Again, this is probably a case of me just watching this movie way too many times, but this score just feels like a bad dream. It’s so damn good that I’m actually impressed that the sequels’ scores even manage to be as effective in its wake. I suppose it’s also no surprise that so many of the later composers also largely opted to do their own thing and just sprinkle in some of Bernstein’s iconic bits here and there. I agree that none of those are as killer as the original’s, but I think each sequel’s score has its own, distinct moment where it comes into its own. I have to admit, though, most of my favorite musical moments from the series evoke Bernstein’s main theme in one way or another.

Come back tomorrow for the final part of this retrospective on A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET upon its 35th anniversary in which we discuss the film’s legacy, its spin-offs, its imitators and…ugh…the remake.

Tags: A Nightmare on Elm Street, Amanda Wyss, Charles Bernstein, Freddy Krueger, Freddy's Nightmares, Heather Langenkamp, John Saxon, Johnny Depp, Jsu Garcia, new line cinema, Robert Englund, Robert Shaye, Ronee Blakley, Wes Craven

No Comments