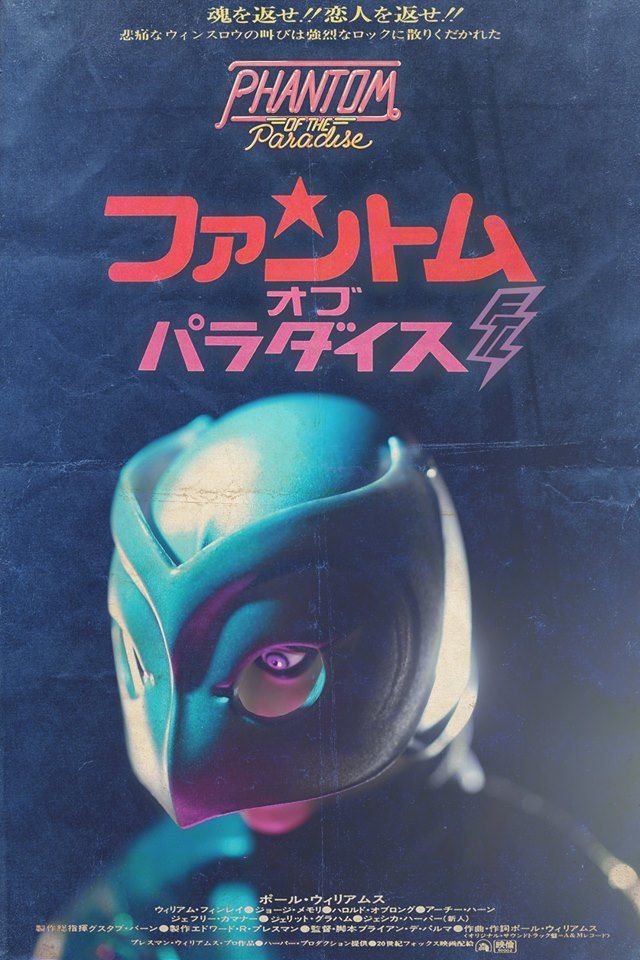

With PHANTOM OF THE PARADISE, director/screenwriter Brian De Palma and songwriter Paul Williams combine The Phantom of the Opera and Faust (with shades of The Picture of Dorian Gray and Frankenstein) to create a rock and roll horror musical. And it’s glorious. Stripped down to its essentials, PHANTOM OF THE PARADISE is the story of Winslow Leach (De Palma favorite William Finley), a songwriter who goes mad with revenge when recording impresario Swan (Williams), steals his music and his muse, a singer named Phoenix (Jessica Harper). Eventually, Winslow (as the Phantom) starts terrorizing Swan’s new nightclub, the Paradise, and Swan is forced to make a deal with him: if Winslow stops trying to kill people, Swan will produce his magnum opus – a rock cantata based on Faust – with Phoenix in the lead role. But there’s so much more here. PHANTOM OF THE PARADISE is a movie about love, obsession, music, artistic integrity, and the perils of trusting anyone in the music business.

What makes PHANTOM OF THE PARADISE work as well as it does it is skill with which De Palma combines and embraces both the musical and horror genres. Musicals and horror movies have more in common than you may suspect. Both are defined by a single element: musicals have songs the way horror movies have death scenes (and pornos have love scenes, but I digress). Regardless of the story, script, direction, design, studio, etc. of any specific movie, it’s that single element that carries a title from the banal “Drama” section in the front of video store to harder-to-find genre shelving at the back, (which is usually near the beaded curtain entrance to the “Adults Only” room, but again I digress). I know that this is a massive oversimplification, but you get my point.

Bearing all that in mind, De Palma first combines music with (attempted) murder in PHANTOM OF THE PARADISE during the song “Upholstery.” Winslow has endured a face-disfiguring accident, and is seeking refuge and revenge (and a costume) at the Paradise, where rehearsals are underway for Faust. As mentioned above, Faust is the rock cantata that Winslow has written and which Winslow auditioned for Swan at the beginning of the film. When Winslow sang it, the song opened like this:

I was not myself last night couldn’t set things right with apologies or flowers

Out of place as a cryin’ clown who could only frown and the play went on for hours

And as I lived my role I swore I’d sell my soul for one love…

Swan takes that same passage and rewrites it as surf rock for the opening of the Paradise, sung by the trio the Beach Bums (Jeffrey Comanor, Archie Hahn, Harold Oblong):

I was not myself last night lost a fight, my woody barely running

By a dude I should have beat, and on the street a blow like that is stunning

I finally lost control and tore my tuck-n-roll upholstery…

Upholstery. Swan changed “one love” to “upholstery.” Winston may be out of his mind and hell-bent on revenge, but after hearing those lyrics, what he does next is one of the most measured and well-reasoned acts of anyone in this film: he plants a time bomb in the scenery, which destroys the set, injuring the singers and some chorus members.

De Palma films the sequence in split screen: backstage on the left, onstage on the right. Backstage, Winslow plants the bomb in the trunk of a prop car about to carry several cast members onstage. Before getting on the car, a chorus girl gets into an argument with Philbin (George Memmoli), Swan’s right-hand man, over her costume, a two-piece bikini. One of the Beach Bums tries to walk off the set because he has a bad feeling and also hears this mysterious ticking noise. Philbin bullies the girl into going on, and literally shoves tranquilizers down the Beach Bum’s throat and pushes him toward the car. This type of backstage drama harkens back to the earliest days of the movie musical – down to the scantily clad chorus girls – and the entire scene is accompanied by the bomb tick-a-tick tick-a-ticking away in time to the music (because that’s how you De Palma).

Musical meets horror even more explicitly at the opening night performance of Faust at the Paradise. The surf rock is gone, replaced by the shock rock of Alice Cooper and KISS. The Beach Bums are back, only renamed the Undeads and wearing black and white make-up. They sing “Somebody Super Like You” while dismembering mannequins and gathering different body parts into a machine to assemble the “Somebody Super” they’re extolling with their song.

Swan has double-crossed Winslow by casting Transylvanian glam rocker Beef (Gerrit Graham, in a virtuosic comedic performance) as the lead of Faust. Beef rises out of the machine, newly assembled, and launches immediately into “Life at Last” (Graham’s vocals are dubbed by Ray Kennedy). The sequence climaxes when Winslow, enraged, electrocutes Beef with a neon lightning bolt.

The musical and horror boxes are both checked (someone sings, someone dies), and De Palma uses the outsized emotions common to both genres to create the kind of set piece that would become his signature: the prom in CARRIE, the opening horror movie of BLOW-OUT, and the running time of SCARFACE.

The cast is excellent throughout. William Finley gives the performance of his career as Winslow, falling from sweet naïveté to righteous fury. Jessica Harper has a wonderful way of underplaying everything while still being the most compelling person on screen. She has a warmly expressive voice and it’s refreshing to see an alto cast as a leading lady in a movie musical.

But it’s Paul Williams who anchors the movie, on and off screen. At the time, was known almost solely as a recording artist (okay and for BATTLE FOR THE PLANET OF THE APES). He is remarkable as Swan, a character who makes you think of Berry Gordy, if he worked for BIM. Swan is constantly manipulating everyone around, but Williams never shows his hand. Williams imbues Swan with the confidence of a man who knows he will get what he wants, because it’s in his contract. Good as he is onscreen, however, it’s his songs on the soundtrack that propel PHANTOM from an interesting failure (which it was) to a genuine cult classic (which it is). Musically, PHANTOM OF THE PARADISE embraces the character-driven storytelling songs common to musicals, as well as an array of rock and roll styles. The two genres combine as the score expands into full-blown rock opera mode for the Faust sequence – at the same time as the horror and movie musical genres culminate in Beef’s murder. As Swan dominates the story, Williams dominates the film.

PHANTOM OF THE PARADISE was a box office failure in 1974 (except in Winnipeg), but it has gained respect and a significant cult following in the decades since. With its themes of social outcasts, authoritarianism, obsession, and voyeurism, it’s an essential entry in Brian De Palma’s filmography. PHANTOM OF THE PARADISE has earned its space on the Great Rock Musicals of the 1970s shelf in the back of the video store, along with JESUS CHRIST SUPERSTAR, TOMMY, HAIR, and THE ROCKY HORROR PICTURE SHOW.

Tags: Archie Hahn, brian de palma, George Memmoli, Gerrit Graham, Harold Oblong, Horror Musical, Jeffrey Comanor, Jessica Harper, Movie Musicals, Musicals, Paul Williams, Phantom Of The Paradise, Rocktoberfest 2019, William Finley

No Comments