[Disclaimer: I have become friends with the filmmakers of TAPEWORM over the years, after first seeing their short films at festivals and championing their works. I don’t believe that colored my reception of TAPEWORM, but it’s important to note and you can find other reviews on Rotten Tomatoes for comparison.]

What is up with Winnipeg? That’s not meant to be a pejorative question, but instead a genuine query about how that city has become so unique. It was the only place where PHANTOM OF THE PARADISE was immediately hailed and recognized for its brilliance upon release. Some of its famous native sons include Let’s Make A Deal host Monty Hall, wrestling elites like Roddy Piper and Chris Jericho, hockey great Brett Hull, and media critic/philosopher Marshall McLuhan. It also has led to some incredibly idiosyncratic voices in film like Guy Maddin, Astron-6 as a collective and with individual works (like THE VOID, from members Steven Kostanski and Jeremy Gillespie), and the cinematic collective of Milos Mitrovic, Fabián Velasco, Ian Bawa, and Markus Henkel.

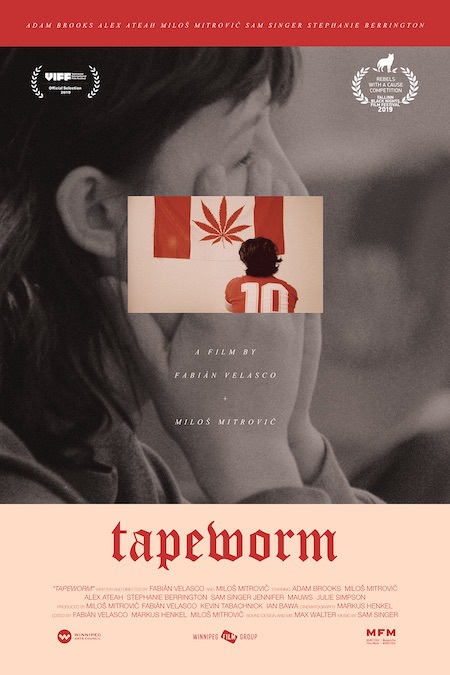

The latter group has mainly made impressive short films, but tackled a feature-length project with their latest title, TAPEWORM. While not as surreal as their shorts, the movie still traffics in similar sense of aloof absurdity that darts back and forth between bathos and pathos, leaving viewers not entirely certain how they should feel about what they just watched.

Having previously played Slamdance 2020, and now available via the filmmakers’ website, TAPEWORM concerns seven people in Winnipeg whose lives are somewhat connected. The opening of the film finds Adam Brooks (playing someone else, there is no character name list) has to go to the bathroom and, upon crapping in the woods, discovers his stool is full of blood and possibly a parasite of some kind.

From there he just wanders in the wilderness before discovering a discarded bed next to a creek where a couple (Sam Singer and Stephanie Berrington) are having sex. Brooks sits down on the edge of the bed and, right before sobbing begins, implores them to not stop what they are doing. It’s an opening sequence that is bizarre without seeming impossible and pretty much sets the tone of TAPEWORM which is dour and odd—potentially to an (intentional) ludicrous degree.

The other four characters are Brooks’ significant other (Julie Simpson) that hates her life (including Brooks), a depressed comedian that is constantly bombing onstage and seemingly about to fall apart (Alex Ateah), a mother (Jennifer Mauws) and son (co-writer/co-director Mitrovic) who seem to hate each other but only slightly less than they hate themselves. So, y’know…fun stuff. Each of these characters are mildly connected to each other (sometimes really just through one scene or so), and mostly it’s a meandering look at the slow boil progression of their loathing as they each alternate between victim and victimizer.

What sub-tier of films that TAPEWORM seems most in dialogue with is the “interconnected” storyline trope from decades ago, but had a boom in the late ’90s and early ’00s. Linklater’s SLACKER and WAKING LIFE, MAGNOLIA, SHORT CUTS (a lot of Altman, honestly), ME AND YOU AND EVERYONE WE KNOW, TRAFFIC, CRASH (2004), HAPPINESS, and Iñárritu’s triptych (AMORES PERROS, 21 GRAMS, BABEL). It rarely works and is usually an overly-forced attempt at dramatic twists that ends up feeling like a forced morality lesson landing with a thud (there are exceptions, including in that list above, but there are also a bunch of examples that prove this).

Co-writers and co-directors Mitrovic and Valesco approach this ensemble motif in a way that undercuts the pillars of this niche trope by showing that overlapping Venn diagrams of experience don’t necessarily lead to epiphanies or transformations, but instead another cog in a wheel of abuse (in one direction or another).

Or perhaps not!

TAPEWORM is incredibly aloof with inserting or asserting its intent. This was evident in the group’s shorts, too, where moments could be deranged and sad, or played for laughs as they may be patently absurd. Do the filmmakers look down on these characters? Do they sympathize with them? Are they mostly indifferent? It’s very hard to say going from scene to scene. There are moments that are so odd and such a leap from logic that it elicited a laugh from me (or at least a guffaw), but then I wondered if I just wasn’t getting TAPEWORM and was laughing at out of nervousness or thinking it inadvertently swung to bathetic (instead of purposefully).

Even if the characters are doing something bizarre—like delivering a seemingly pointless anecdote about an old acquaintance for a long stretch or just pissing on the neighbors’ door—there is a lived in and real quality to their humanity brought out by the actors. The people aren’t always likable or logical or enjoyable, but it’s not hard to look at these characters and recognize folks you’ve encountered in your life (or mirror). TAPEWORM also excels by constantly shifting dynamics of sympathy, showing a complexity to the toxic relationships. It never feels manipulative or like some cinematic version of that Everlast song, but instead allows for growing understanding of this world.

TAPEWORM is all muted colors and passive aggression, taking place with people minimized in frame amidst their beige surroundings and metastasizing despair. Mitrovic and Velasco don’t bluntly state that they are parodying a certain type of films, nor are they blatantly trying to revitalize that subset with a grim new take. That remoteness means that audiences may feel uncertain of where the film is going or how they should be viewing it.

Is it a Todd Solondz-esque dark comedy about this rage turned inward flaring up outward to the people closest to us? Or is TAPEWORM a meditation on how we all seem to have problems but remain uncertain how to fix them or at least improve the situation? That lack of definition means that, in the moment, TAPEWORM can feel longer than it is (a brief 78 minutes) as viewers are left to discern the point or intent of any of this.

But, to TAPEWORM‘s credit, it has stuck with me for weeks after watching it. Daily Grindhouse contributor Justin Yandell has often discussed how film reviews (especially festival reviews) aren’t conducive to great analysis because it’s about quick turnaround and getting it out there as soon as possible.

By having time to sit with TAPEWORM, I replay scenes and lines, pondering how they fit into a certain thesis or overarching schema. It can be frustrating in the moment, but the film ends up lingering as the mind goes back over moments and tries to see if there’s a gestalt at work.

TAPEWORM isn’t so weird that it’s a bonkers hidden gem, and it’s not so dark or cruel that it’s for the joyless gluttons of misery, either. It’s an odd beast that is hard to recommend unless you are willing to wander a story without much of a guide and are okay with questioning it for days afterward. And, like so much that has come out of Winnipeg, TAPEWORM has moments of intersection with the familiar, but remains a fairly singular experience.

TAPEWORM played Slamdance 2020 before the massive change in the world. It is now available to watch and rent through the filmmakers’ website, found here. For those looking to support unique and independent cinema, please consider checking it out.

Tags: Adam Brooks, Alex Ateah, Canada, Dave Barber, Fabian Velasco, Ian Bawa, Jennifer Mauws, Julie Simpson, Manitoba, Markus Henkel, Milos Mitrovic, Sam Singer, Slamdance 2020, Stephanie Berrington, Winnipeg

No Comments