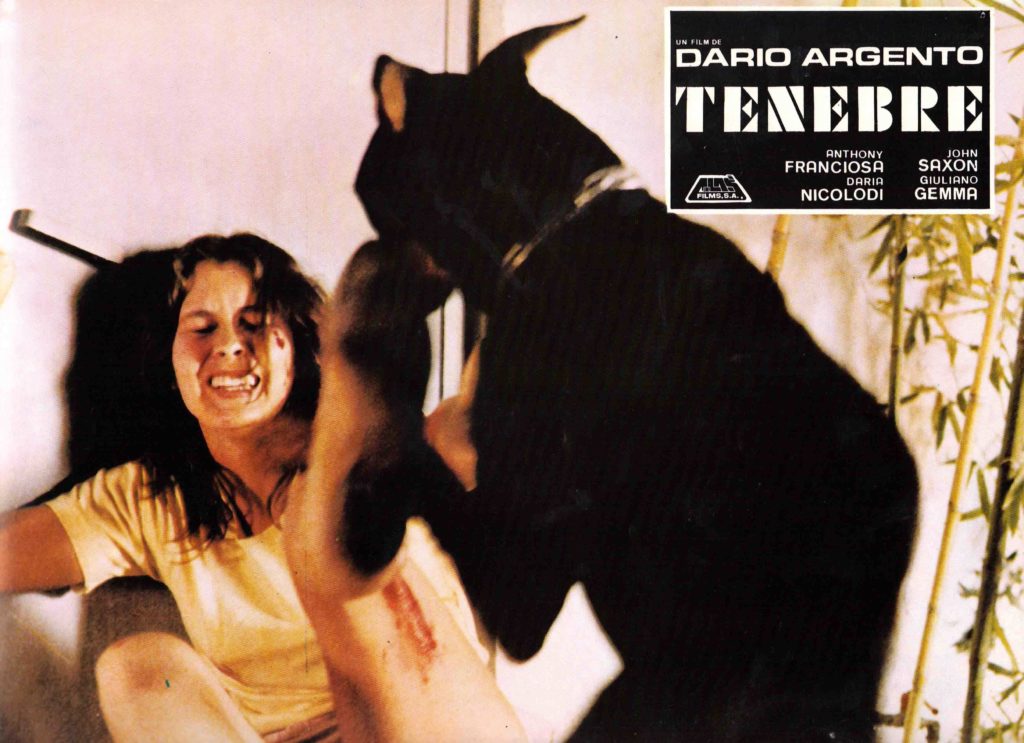

Title: THE LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT

Other Titles: SEX CRIME OF THE CENTURY; KRUG AND COMPANY; THE MEN’S ROOM

Year: 1972

Director: Wes Craven

Cast: Sandra Peabody, Lucy Grantham, David A. Hess, Fred Lincoln

Nasties:

Rape

Stabbings

Arm amputation

Disembowelment

Skin carving

Mid-fellatio castration

Gunshot to the head

Switchblade to the face

Chainsaw to the everything

“All that blood and violence. I thought you were supposed to be the love generation.”

– Estelle Collingwood, THE LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT

Violence, in all of its forms, is part-and-parcel of the revenge exploitation film. Audiences whoop and holler as Foxy Brown lays out a hefty dose of retribution, a fascinating facet of viewer identification that continues to this day in mainstream hits like DJANGO UNCHAINED (2012). Once in a while a movie comes along that utilizes violence and genre limitations to distill ugly (but necessary) social commentary from a simple narrative. In 1972, Wes Craven did just that, and knocked one out of the park with his directorial debut, THE LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT.

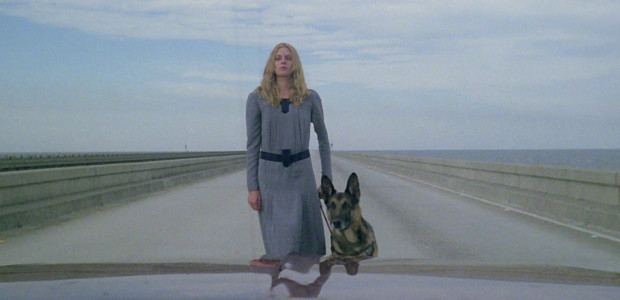

The film follows two teenage girls, Mari and Phyllis (Sandra Peabody and Lucy Grantham) who comes across a small gang of thugs: diabolical leader Krug, his girlfriend Sadie, sex fiend Weasel, and Krug’s dim-witted son Junior. The gang inflicts unspeakable atrocities upon the two young women and when the parents of one of the girls run into the same gang later, they decide to dispense their own justice.

Not only are all major characters in the film fully formed (a rarity among the Video Nasties), but they are allowed vulnerability, even the villains. In fact, one of the most iconic scenes in the film comes after Mari’s rape and mutilation, when the assailants stand around in a haze of disgust at their acts. The camera lingers on their shameful faces while they avoid each other’s gaze and make feeble efforts to clean the blood off of their hands. They’ve gone too far; their innocence is forever lost. David A. Hess, Fred Lincoln, and Jeramie Rain deliver chilling performances as Krug, Weasel, and Sadie, with an equally sympathetic execution from Marc Sheffler as Junior. Without their collective villainy, audiences wouldn’t be rooting for the avenging parents as vociferously as they do. Likewise, Cynthia Carr and Gaylord St. James shine in their roles as John and Estelle Collingwood, insufferable bourgeois stuffed-shirts who are equally convincing as grieving, furious parents.

Wes Craven’s movie is inspired by Ingmar Bergman’s THE VIRGIN SPRING (1959), which was based upon Ula Isaksson’s novel, which was in turn based upon a medieval ballad. Both films feature savage atrocities visited upon young women whose otherwise peaceful loved ones, once provoked, turn to rage-filled revenge. There are, however, more than enough creative alterations to the narrative to keep the term “ripoff” at bay, particularly when it comes to the final outcome (the patriarch of THE VIRGIN SPRING ends on a hopeful note, resolving to build a church, while LAST HOUSE has a more nihilist, GREEN ROOM-ish resolution). Make no mistake, though: THE LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT is exploitation, albeit with something to say. In fact, the genre’s blunt-force delivery lends itself to the serious implications it makes with regard to vengeance, toxic patriarchy (via Krug and Junior’s relationship) and even violence as part of the human condition. Perhaps that’s how the more transcendent rape-revenge exploitation films (MS. 45 comes to mind) are able to get away with such resounding condemnations of society; those condemnations are often cloaked within the structural absurdities of the genre.

BOLDNESS

A film that displays a connection between the transgressor and the righteous avenger is, like DEATH SENTENCE (2007), bound to hit hard and cut deep. THE LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT does not hold back in its audience immersion of Mari’s torment, nor does it pull any punches in its brutality visited upon Krug and his cohorts. The first bit of violence occurs 18 minutes in as one of the victims (Phyllis) is gut-punched and subjected to an off-screen rape. From there follows a descent into barbarity from the gang and from Mari’s parents. LAST HOUSE departs from the usual exploitation film approach by focusing less on the actual rape and more on the lust for power and subsequent humiliations visited upon the victims. The sexual assaults themselves are edited but the unflinching savagery remains undiluted. Krug doesn’t just attack these women, he forces them to undress and fondle each other. The gang doesn’t just violate Phyllis, they coerce her into urinating on herself and mock her as she stands before them, her pants soaked. There’s more repulsiveness in the threads of saliva extending from Krug’s mouth as he pulls away from his victim, than in the implied penetration he’s inflicting upon her just offscreen. The most jarring instant occurs when a character has his penis bitten off in the middle of an uncomfortably tender moment. As a bonus, the movie’s bloody climax showcases a power-tool death scene that pre-dates TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE by two years.

Bold as it is, Craven’s final product was initially more audacious. The 2003 Anchor Bay DVD edition of LAST HOUSE featured a short documentary, Celluloid Crime of the Century, which gave a quick glimpse of the original 1971 script (titled NIGHT OF VENGEANCE). This script included scenes of cannibalism and lesbian sexual assault that were later edited out for being too hardcore.

SENSATIONALISM

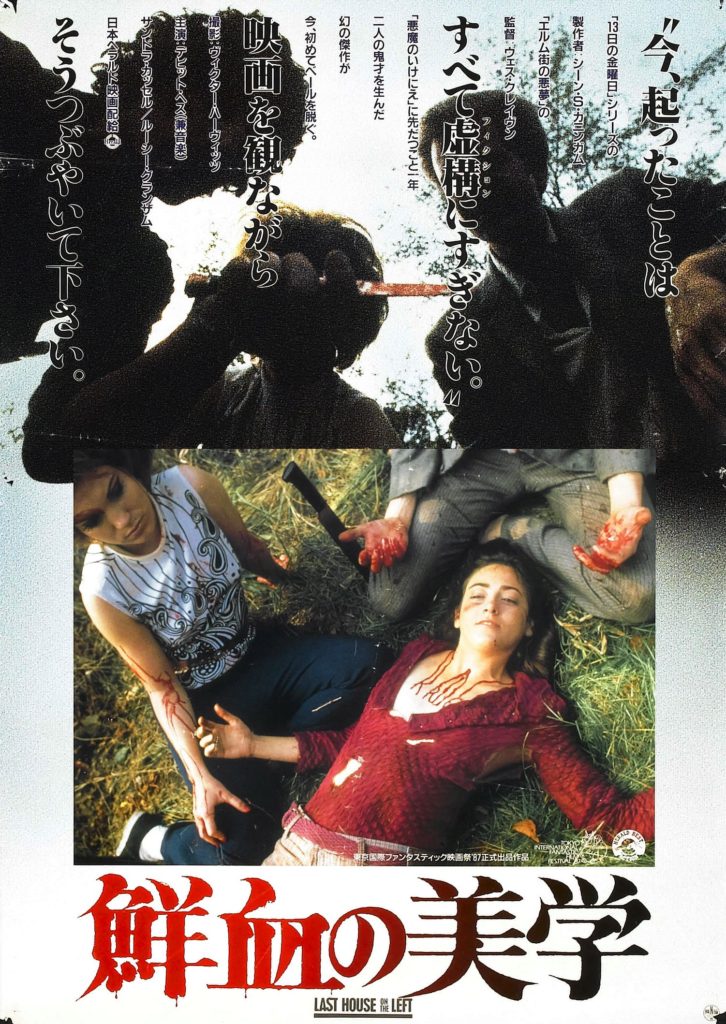

Upon its initial release, LAST HOUSE was outright rejected for theatrical certification but had no problem getting an uncut video release in the early 1980s. The controversy surrounding the film resurfaced in 1984 with the passage of the Video Recordings Act. The Department of Public Prosecutions branded LAST HOUSE as a Video Nasty and immediately banned the film in the UK. The film remained outlawed for over a decade despite having a heavy cult following and vocal proponents defending its artistic merit in the media. It was submitted for and refused certification multiple times over the years until July of 2002, when it snagged an ’18’ certificate (with 31 seconds of cuts). Its subsequent Blue Underground DVD release was in May of 2003. The BBFC classified the uncut version of the film for video release in 2008

Across the pond, Wes Craven took his film to the MPAA for rating. They slapped it with the dreaded X rating, limiting its scope of release. Undaunted, Craven went back and removed ten and later twenty minutes of footage in an effort to get the American certification authority to dial it down to an R rating. It didn’t work; LAST HOUSE still got a hard X. Finally, Craven resubmitted the film, this time with all of the original footage intact. It worked. He got an R rating and a wide release.

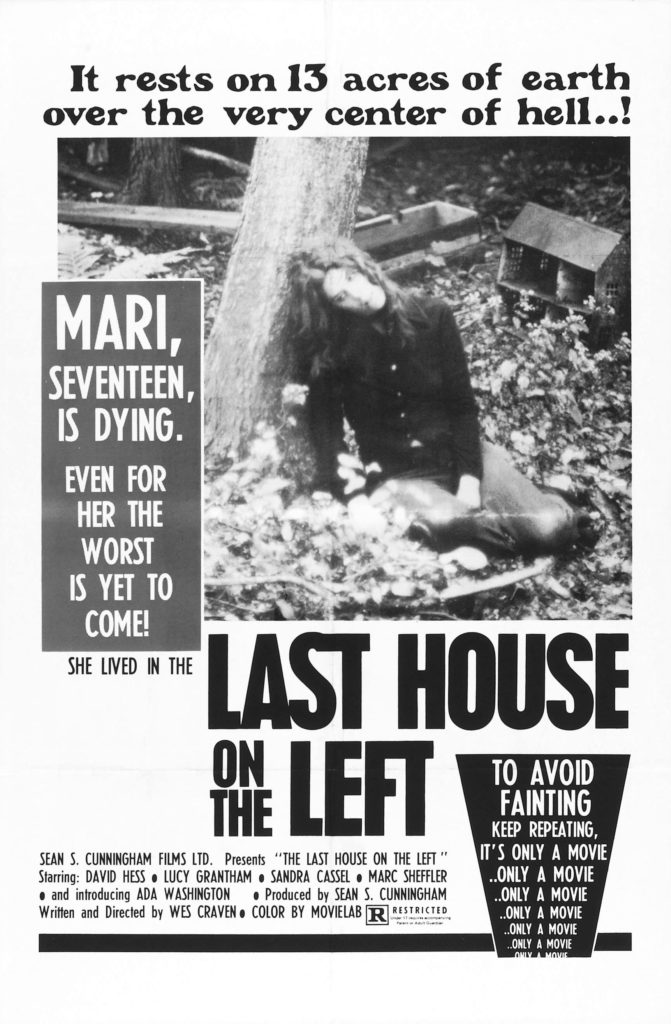

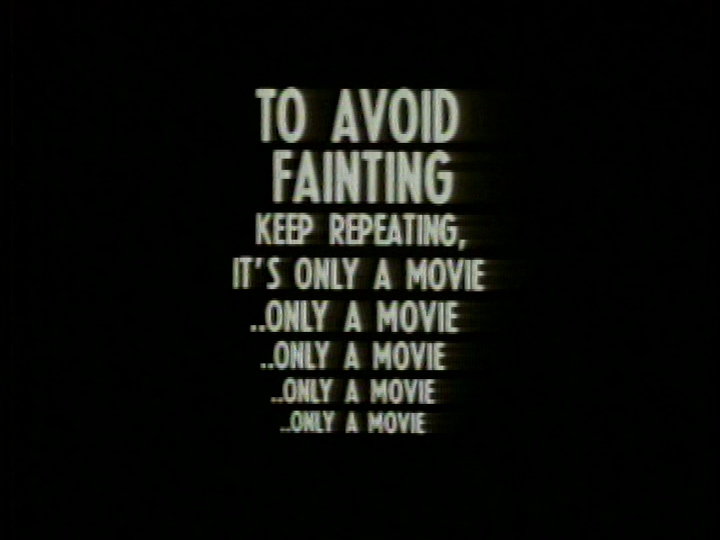

LAST HOUSE’s trailer has become iconic itself. A sunken voice solemnly tells of a place located “over the center of Hell” as images of fleeing women flash on the screen before the narrator exhorts the audience to keep repeating to themselves: “It’s only a movie. Only a movie. Only a movie.” Alongside the promo tagline “WARNING: Not Recommended for Persons Over 30,” it’s clear that the promoters at Hallmark Releasing knew very well how to run the exploitation angle for box-office success. After all, these were the same folks who went full carnival-barker to promote Mario Bava’s A BAY OF BLOOD the same year, by requiring theaters to warn patrons face-to-face of the horrors they were about to see.

SHELF LIFE

THE LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT resonates for both its shocking nature and its boldness in strapping the viewer down and immersing them in the experience of both violator and victim. Notable film critic Roger Ebert, in a rare turn in defense of a horror film, gravely praised the film as “…a movie of worth, of a certain dogged commitment to its unsavory content.” For once, Ebert’s right about a genre film. In the realm of exploitation cinema (that is under no obligation to be anything more than pure shock and depravity), THE LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT dares to uncover a social subtext simmering underneath its very human characters. It blurs the line between good guys and baddies by revealing a common, violent thread that is innate to every living human. Craven’s use of ultraviolence to confront audiences allowed him to couch moral forebodings within a narrative that would have been preachy in any other (more mainstream) genre, a method that paved the way for films like THE EXORCIST (1973) to graphically provoke its viewers down the road. Its importance in the horror genre cannot be understated.

Then again, it’s only a movie.

VIDEO NASTIES ALREADY IN THE BIN:

REVENGE OF THE BOOGEYMAN (1983)

Tags: Columns, David A. Hess, Fred Lincoln, Horror, Lucy Grantham, Sandra Peabody, The 1970s, VHS, Video Nasties, violence, Wes Craven

No Comments